In the depths of American sports, some pioneers are celebrated, their stories woven into the complex fabric of national identity. Others, like Frederick Douglass “Fritz” Pollard, operate in the penumbra of history — their foundational struggles and monumental achievements dimmed by time and institutional neglect.

As we celebrate Black History Month, the story of this Indianapolis-connected trailblazer is not merely one of athletic genius but a masterclass in perseverance against the machinery of segregation, a narrative of a man who didn’t just break barriers on the gridiron but built entire enterprises off it when those barriers proved unmovable.

Pollard’s journey began not in a field but in a pioneering household in Chicago’s Rogers Park neighborhoodas the son of a Civil War veteran and a savvy entrepreneur.. His siblings set formidable precedents: the first Black woman to graduate from Northwestern, the first Black registered nurse in Illinois and a pioneering film producer.

For young Fritz, athletic prowess became his avenue. At Lane Tech College Prep High School, his speed made him a standout. Yet, he faced segregation early. Once, his own coach spirited the team away on an earlier train to avoid telling Pollard an opponent refused to play against a Black athlete.

The “Human Torpedo”

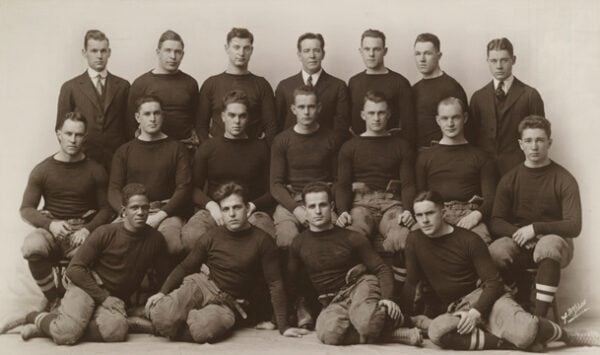

His arrival at Brown University in 1915 placed him at the epicenter of elite, white athletic culture. At 5’9″ and 165 pounds, Pollard was undersized yet unstoppable, earning the nickname “Human Torpedo.”

The hostility was visceral; fans taunted him with songs like “Bye Bye Blackbird.” Pollard often needed police escorts to evade bricks and bottles lobbed from the stands.

Pollard adopted a tactical grin, famously stating he would simply look at his detractors “and then run for an 80-yard touchdown.” During the 1916 season, Pollard led Brown to an 8-1 record, engineering historic first-ever victories over both Yale and Harvard in a single season.

His performance — rushing for 144 yards against Yale and 148 against Harvard — was so transcendent that Walter Camp, the “father of American football,” named him the first African American running back to his All-America team, calling him “one of the greatest runners these eyes have ever seen.” His collegiate career crescendoed with Pollard becoming the first Black player in the Rose Bowl on Jan. 1, 1916.

A professional pinnacle and shattered ceiling

Pollard’s transition to the professional ranks was as historic as his collegiate tenure. In 1920, he and Bobby Marshall broke the color line as the first African American players in the newly formed American Professional Football Association, a precursor to the NFL. As the star running back for the Akron Pros, Pollard led the team to an undefeated 8-0 (and three draws) record and the league’s first championship, outscoring opponents 151-7.

In 1921 the Akron Pros named him head coach, making Pollard the first African American to hold the position in NFL history.

Pollard’s milestone would stand alone for nearly 70 years.

He was a player-coach, navigating the complex dynamics of leading white teammates in a segregated society. He later broke another barrier as the first Black quarterback for the Hammond Pros, a team based in Northern Indiana, in 1923, directly challenging stereotypes concerning Black intelligence and leadership on the field.

Exile and enterprise

Pollard’s pioneering era was cut short. In 1933, NFL owners instituted an informal “Gentleman’s Agreement,” an outright ban on Black players that erased them from the league until 1946. Pollard’s response was quintessential: if the door was barred, he would build his own.

Pollard founded the Harlem Brown Bombers in 1935, an all-Black barnstorming team named for Black boxer Joe Louis. The Brown Bombers were a spectacle and a statement, assembled to prove the absurdity of the NFL’s “lack of talent” justification. They dominated the minor league circuit, decimating white professional teams and Army All-Star squads. Yet, NFL clubs refused to schedule them, fearing a loss would undermine the very rationale for the color line.

Undeterred, Pollard expanded into media and business. He published the New York Independent News, a Black weekly with a circulation of 35,000 that championed civil rights and covered Black athletes ignored by the white press. He founded one of the first Black-owned investment firms, operated a talent agency for icons like Lena Horne, managed a Harlem rehearsal space for Duke Ellington, and even pioneered “Soundies,” a precursor to music videos.

Pollard’s legacy in Indy

For Indiana, and for the Indianapolis Recorder, which tracked his career, Pollard’s legacy breathes in the Hoosier State. His tenure with the Hammond Pros in the 1920s made him a fixture in the state’s sports history. The Recorder diligently documented not only his career but also his son, Fritz Pollard Jr.’s, athletic feats, a track star who competed in the 1936 Berlin Olympics.

In 2003, advocates founded the Fritz Pollard Alliance (FPA), an organization dedicated to promoting minority hiring in coaching and front-office positions. The FPA was instrumental in creating and advocating for the Rooney Rule, requiring NFL teams to interview at least one (now two) diverse candidates. Today, the alliance also grades teams on hiring practices and runs accelerator programs.

Pollard’s story is one of cyclical progress — early breakthroughs, deliberate erasure, and a long, hard road to reclamation. Finally inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 2005, Fritz Pollard is no longer just a football footnote. He is a seminal American figure whose life reminds us that the battle for equity is fought not on one field, but on every field where talent is denied its chance to shine.

Contact Multimedia Reporter Noral Parham at 317-762-7846 or email at noralp@indyrecorder.com. Follow him on X @3Noral. For more news, click here.

Noral Parham is the multi-media reporter for the Indianapolis Recorder, one of the oldest Black publications in the country. Prior to joining the Recorder, Parham served as the community advocate of the MLK Center in Indianapolis and senior copywriter for an e-commerce and marketing firm in Denver.