A proposal to build a data center on a long-vacant lot in the historic Martindale Brightwood neighborhood ignited a fierce debate, pitting promises of economic investment against deep-seated community fears of environmental burden and displacement.

For many Hoosiers, the plan from Los Angeles-based developer Metrobloks isn’t a story of progress, but a familiar pattern of imposing industrial infrastructure on a low-income, historically Black neighborhood.

The site at 2505 North Sherman Drive, once home to the Sherman Drive-In Theater, has been empty for more than four decades. Metrobloks argues that their facility would reactivate this dormant site, bringing new economic activity through a sound-attenuated, closed-loop water-cooling system. For City-County Councilor Ron Gibson (D-District 8), this is an opportunity too crucial to pass up.

“For more than 40 years, this property has remained unused, contributing little to the local economy or the quality of life,” Gibson said in a statement. “The proposed data center represents a rare and significant opportunity to transform this longtime dormant site into a productive, modern asset.”

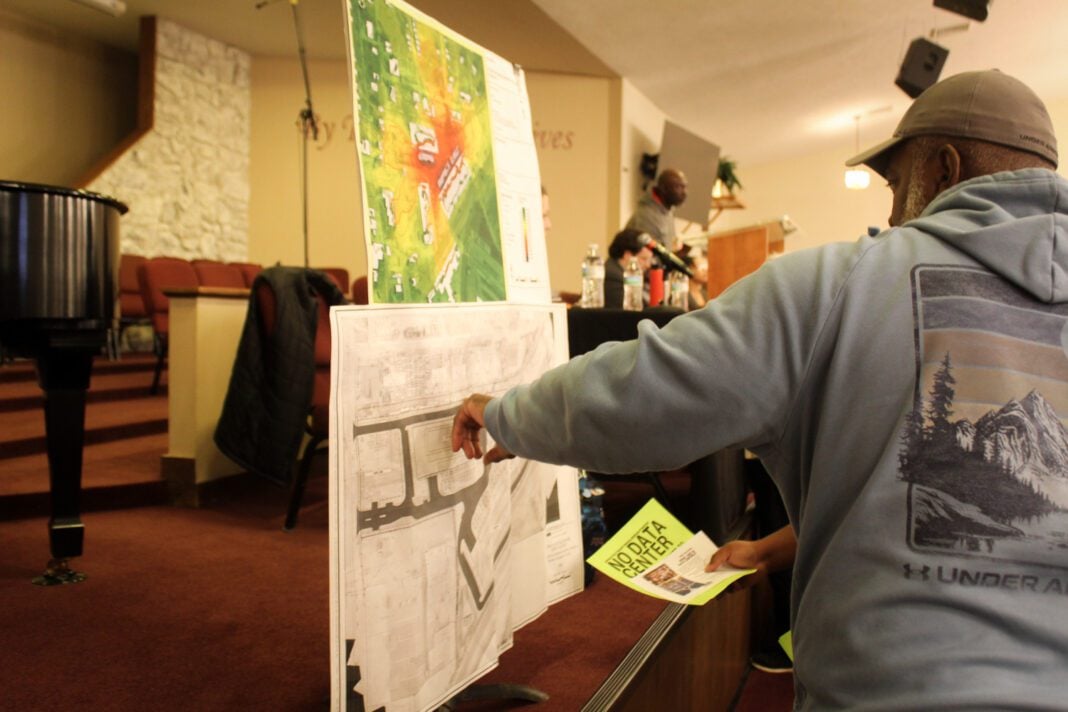

However, for hundreds of residents who packed the Fredrick Douglass Community Center for a tense meeting on Feb. 2, the developer’s assurances rang hollow. Their message, as summarized by One Voice neighborhood advocacy group president Cierra Johnson, was direct:

“What we want is them to go home.”

The core of community members’ opposition lies in the tangible impacts of data centers: massive electricity consumption for 24/7 server operation and significant water use for cooling, even in closed-loop systems that require constant replenishment due to evaporation. Residents fear these demands strain local grids and water resources, potentially leading to higher utility costs for surrounding households — a hidden tax on a community already facing economic pressure.

“This is disheartening, and knowing that they’re intentionally putting it in low-income, poverty-stricken areas, it’s very much intentional,” community member Camille Walker said. “We’ve seen this before: they built factories that cause cancer near our communities. So, we know this is not anything new.”

Walker’s perspective adds a complex layer to the discussion. As the owner of Lamira Wellness and its subsidiary Lamira AI, where she works as a data annotator and AI ethics integrator, she is not opposed to technology. Yet, she stands firmly with her neighbors in questioning the ethics of this specific proposal.

Echoing these comments are residents like Rev. Shonda Nicole Gladden, a homeowner in Martindale Brightwood, who points to the potential for direct harm.

“It is not only impractical to build a data center in my dense, residential, historically Black neighborhood, but given its high potential for ecological disruption, it is also unethical and profoundly ill-advised,” Gladden said. “Research shows that Black communities near data centers and associated power plants are already reporting worsened air quality, increased respiratory risk and disruptions to everyday life, which compounds long histories of environmental harm.”

Gladden’s stance underscores a key community demand: rigorous, independent scrutiny before any approval.

“Before any data center is approved here, our community deserves full transparency on projected water and energy use, independent health and environmental impact assessments, and enforceable protections against bill spikes,” Gladden said.

Walker argues the entire conversation must shift from convincing the community to accept the project to compelling the company to meet strict, community-beneficial conditions.

“If you are building this data center in our community, here are the conditions … We need to be pushing these companies to be doing more ethical consumption of energy” Walker said.

For a community with a history of facing systemic disinvestment followed by potentially disruptive development, the data center proposal may feel less like an opportunity and more like an imposition. Some fear that the neighborhood will bear the brunt of the environmental and economic upheaval. At the same time, some residents are concerned the benefits — tax revenue, high-tech prestige—will flow elsewhere.

The Metrobloks proposal is scheduled for a hearing before the Metropolitan Development Commission hearing examiner on Feb. 12. As that date approaches, residents of Martindale-Brightwood are making it clear that true development must be measured not just in servers and investment dollars, but in community health, stable costs and a respected voice in their own future.

“If we are going to integrate AI into our neighborhoods, then we must do it right,” Walker said. “We must integrate AI ethically.”

Contact Multi-Media Reporter Noral Parham at 317-762-7846. Follow him on X @3Noral. For more news, visit indianapolisrecorder.com.

Noral Parham is the multi-media reporter for the Indianapolis Recorder, one of the oldest Black publications in the country. Prior to joining the Recorder, Parham served as the community advocate of the MLK Center in Indianapolis and senior copywriter for an e-commerce and marketing firm in Denver.