In the words of Black writer and poet Maya Angelou, “You can’t really know where you’re going until you know where you have been.”

Having a fundamental understanding of history informs people of how and why the world works the way it does, said Charlene Fletcher, Frances Shera Fessler Assistant Professor of History, affiliate faculty in the Race, Gender, and Sexuality Studies (RGSS) Program at Butler University. With the current political climate and national DEI rollbacks the role of Black historians, archivists and preservationists — our “keepers of culture” — is more crucial than ever.

“If we would all read the constitution, we might know what can be done and who has the power to do what,” Fletcher said. “It’s important for us to understand those foundations, what has happened in the past, so we can be better, and we don’t repeat these things.”

One of the key aspects of Black culture lies in the acknowledgement of “those who come before us,” Fletcher said. She always wanted to be a historian and said “Don’t Eat the Pictures: Sesame Street at the Metropolitan Museum of Art” sparked her interest in ancient Egypt and the afterlife.

READ MORE: Guy’s Cooking Creation: Sauces, seasonings and serving community

Her grandmother nurtured her natural curiosity, taking her to the Zion Hope Baptist Church bookstore to purchase every book on Egypt — even the ones above her reading level — and read them together.

“Many of us understand that we stand on their shoulders,” Fletcher said. “But understanding that the things that we are experiencing in our current moment, our ancestors have been here before and oftentimes in much uglier spaces.”

However, it’s the recognition and reverence of one’s ancestors and elders that shapes their understanding of the world and, by default, their culture.

Eunice Trotter, Director of Indiana Landmarks Black Heritage Preservation Program, echoed this sentiment and said history is the “foundation upon which the present is built.”

“When you don’t know where you’ve come from, don’t know the history, you are like sinking sand,” Trotter said.

Trotter has been with Indiana Landmarks since 2022, but her formal educational background is journalism. She said journalists possess all the qualities needed to be historians, such as writing, research, documentation and tenacity.

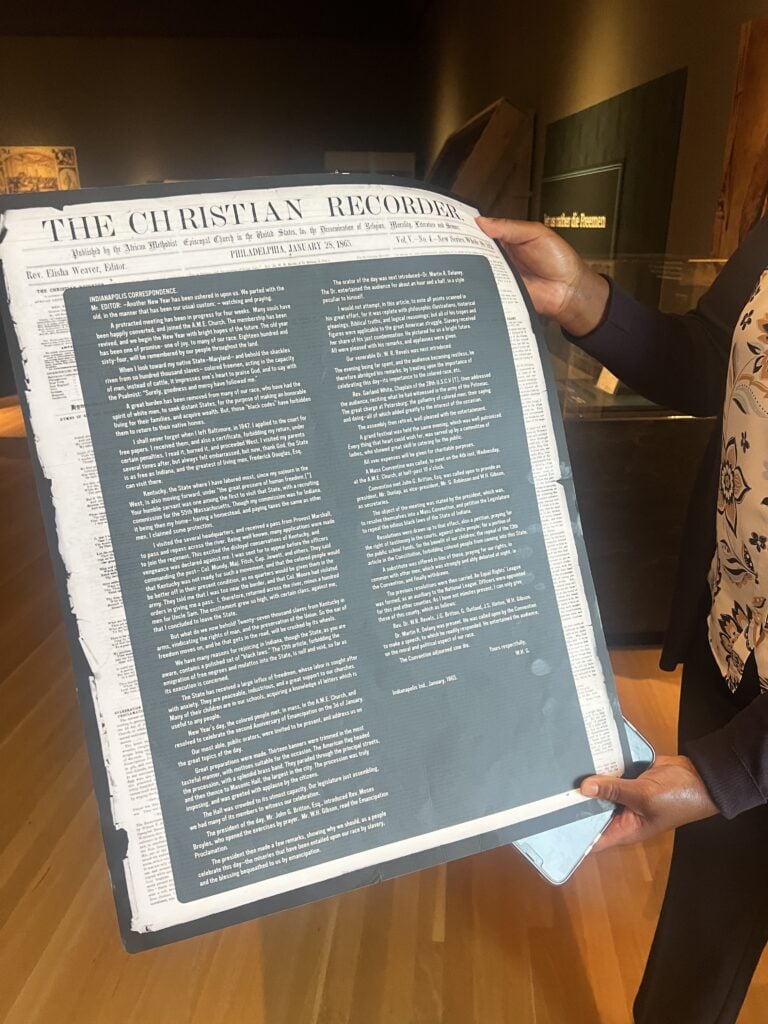

After 50 years in journalism, including four years as owner, editor and publisher of the Indianapolis Recorder, the fourth oldest Black newspaper in the U.S., Trotter said the transition from reporting to archiving was easy. After all, her work as a historian and genealogist isn’t dissimilar to her work as a journalist.

“For history and for journalism, it’s all about the sources of information,” Trotter said. “There are many, many sources of information out there that journalists don’t tap into that I learned about as I got deeper into historic research, and that historic research is also tied to genealogy.”

Trotter got into genealogy — the study of families, their personal backgrounds and lineages — when researching her own family. That’s when she discovered her great-great-great-grandmother, Mary Bateman Clark, was involved in an Indiana Supreme Court case that “should be in state history books,” Trotter said.

READ MORE: Mary Bateman Clark helped end slavery, indentured servitude in Indiana

Clark, who was sold into indentured servitude in Vincennes, Indiana, in 1816, won her freedom at the Indiana Supreme Court with the help of abolitionist lawyer Amory Kinney in 1821. Clark’s case set a precedent in the State, and Trotter’s research into her ancestor’s life led to the placement of a historical marker in Vincennes.

Kisha Tandy, curator of social history at the Indiana State Museum, said having an understanding, awareness and knowledge of “our history” serves as a foundation that can move people further. Tandy, a researcher specializing in Black history in Indiana, grew up an avid reader in Indianapolis and said it was the city’s rich history that inspired her to become a historian.

“I can look to the past to help me move further, to help me grow, help me to keep going,” Tandy said. “I am inspired by the past. I’m encouraged because there is so much resilience. There is so much resilience, and it is through this resilience that we keep pressing on toward the goals, that we keep moving, that we keep working, that we keep going in search of finding ways to improve life in the community.”

Tandy is “always looking in the past,” and studying organizations, like the Women’s Improvement Club (WIC), an exclusive organization for prominent Black women professionals from 1903-1980. Her understanding of Black history and culture is shaped by resilience and the ways in which community was important for growth. Evidence of this is seen throughout stories and moments in history in Indianapolis, including as WIC, Tandy said.

Due to their longevity, a lot of the research Tandy does for the Indiana State Museum can be found by simply looking through the pages of the Indianapolis Recorder and other Black newspapers. Whether it’s digitized news articles at the Hoosier State Chronicle or physical papers on microfilm at the Indiana State Library, Tandy said written documentation about people’s lives is “always essential.”

“It is always so important to have history, to collect history, to document history … because we do know people will be using it in the future,” Tandy said.

Tandy spends a lot of time talking with older members of the community because they have knowledge that “I won’t ever have,” unless someone tells her. However, that doesn’t mean the work is easy.

“It’s a calling, for sure,” Fletcher said. “When you’re doing this work, it’s not easy because these histories — they’re ugly, they can be. You may find things or learn things that are extremely painful, don’t shy away from them, grapple with them.”

These stories need to be identified and told, Fletcher said, even when elders in the family or community don’t want to talk about them.

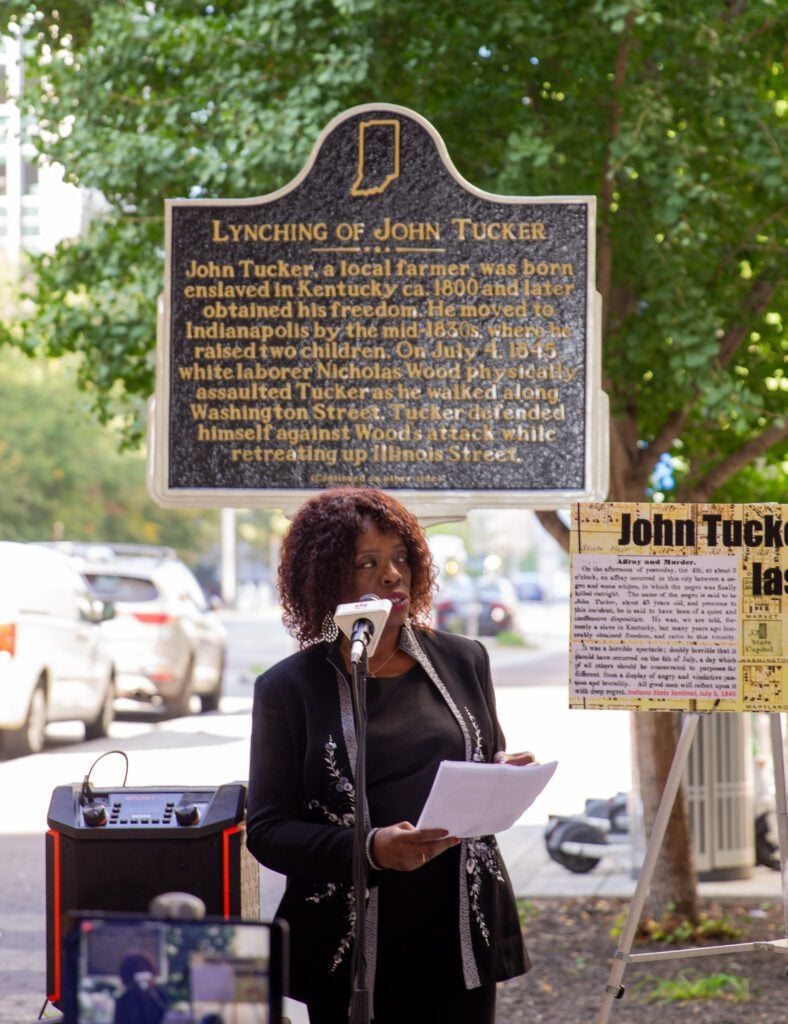

“I could talk to you for four days in a row, but preservation of Black history is so important because of erasure,” Trotter said. “When all evidence of a historic person, a historic site, a historic event, is erased, so goes the information and the benefit of knowing that information. So, if you don’t preserve it, it disappears.”

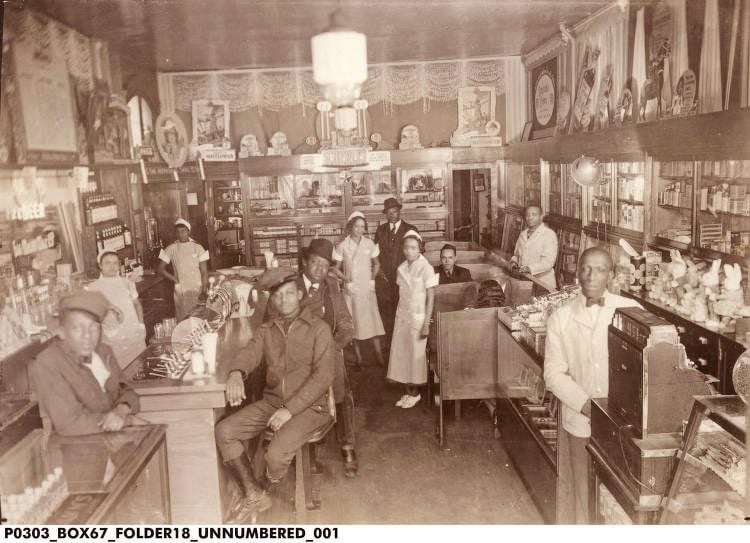

Whether it’s displaying a Black soldier’s uniform in a museum, preserving a young woman’s scrapbook from the 1920s or collecting fliers and t-shirts throughout social and civil movements in time, documenting Black history will always be essential, Tandy reiterated.

“These are the things we are going to use to tell stories and to share what has been done in the future,” Tandy said.

Contact Arts & Culture Reporter Chloe McGowan at 317-762-7848. Follow her on X @chloe_mcgowanxx.

Chloe McGowan is the Arts & Culture Reporter for the Indianapolis Recorder Newspaper. Originally from Columbus, OH, Chloe has a bachelor's in journalism from The Ohio State University. She is a former IndyStar Pulliam Fellow, and has previously worked for Indy Maven, The Lantern, and CityScene Media Group. In her free time, Chloe enjoys live theatre, reading, baking and keeping her plants alive.