Editor’s note: This is part two in a three-part series. Click here for part one, “How to Increase Black Productivity and Racial Equity and here for part three, Prioritizing Racial Equity for Inclusive Prosperity.”

Quality education, ownership of land, homes and businesses, along with consistent access to capital, all form the foundation of an economic infrastructure needed to build generational wealth. This formula isn’t new. It is how white Americans built the U.S. economy and how Black Americans built prosperous communities following the Civil War, after the last enslaved Black people left the plantations of Galveston Island near Houston, Texas, on June 19, 1865 (a.k.a. “Freedom Day” and “Juneteenth”). The iconic Statue of Liberty remains a daily reminder of the death of chattel slavery and freedom for Black people in the United States. But freedom did not deliver economic opportunity and empowerment of

Black people in a hostile whites-only nation in 1865. That required multiple acts of Congress, including a new Freedmen’s Bureau, a Civil Rights Act and three changes of the Constitution … all within a span of less than seven years.

History Matters

The Freedmen’s Bureau, established by Congress in 1865 and managed by the Department of War, was the first economic strategy established by white progressive “radicals” to develop an infrastructure for 4 million newly freed Black refugees freed from bondage and entering into a whites-only nation with a whites-only citizenry with whites-only institutions of power, wealth and influence. The Freedmen’s Bureau was the federally funded source for Black people to receive land, homes, education, workforce training, entrepreneurial opportunities, jurisprudence and protection within a landscape of white hostilities. It was immediately attacked by white supremacists who insisted the nation remain a whites-only country. President Andrew Johnson was the lead antagonist.

In 1872, the Amnesty Act empowered white supremacists to regain power in Congress, and they immediately cut funding for the Freedmen’s Bureau. In 1877, the secretive “Great Compromise” between northern whites and southern whites resulted in the removal of troops from the South. And by the time the Supreme Court in 1896 officially declared two separate, distinct Americas — one white, wealthy and powerful, the other Black poor and powerless — there had been at least 53,000 documented murders of Black Americans over a 30-year period. That’s 147 murders a month … roughly five every day. White terrorism reigned in the south, which triggered a Great Migration to northern and western states that would last for 70 years.

Black Prosperity

Yet, in the midst of such widespread domestic terrorism, some Black communities found ways to prosper. The familiar economic foundation of education, ownership and access to capital were key elements. Prosperous communities were born, known as “Black Wall Street.” While Wilmington, North Carolina, and Tulsa, Oklahoma, were extraordinarily prosperous, both were targeted and attacked by white mobs and completely destroyed. In between the destruction of Wilmington in 1898 and the Greenwood community in Tulsa in 1921, there were dozens of white riots in cities large and small across the nation. In 1919, a.k.a. the “Red Summer,” 36 cities were under siege. And, Black families either fled or fought for their lives.

In the 1950s and ‘60s, the federal government started offering local economic development planners 90% of the cost to build freeways out to newly developed suburbs the feds also subsidized through a process called “urban planning.” At the same time, governments, banks and the real estate industry incorporated a process of “red lining” that impeded both homeownership and access to capital for Black families, including most who could afford to live in suburbia. Meanwhile, the Economic Development Administration (EDA) introduced a strategy for developing prosperous communities that also ignored Black America. The Civil Rights Movement rose up during this era of economic sanctions and starvation of Black America.

Black Innovation

Nevertheless, Black innovation, creativity and tenacity would not be stopped. In a 40-year span following the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968, Black entrepreneurship skyrocketed from 187,000 Black-owned businesses in 1972 to more than 2.6 million in 2012. Yet, despite this phenomenal rate of Black entrepreneurship, the productivity output remained less than 1 percent of GDP, precisely where it has been for more than 100 years.

Despite poor quality schools relegated to serve poor Black communities and the most vulnerable populations across Indiana, the problem of generational poverty cannot be blamed on a lack of Black creativity, innovation and risk-taking to establish, grow and scale businesses that can produce jobs and wealth. The problem today is, as it has been from the end of the Civil War, the structure of public and private sector policies and practices which deny critical investments to build an economic foundation and infrastructure conducive to fostering the growth of business and sustainable prosperity in Black communities.

Today, Accelerate Indy is the kind of economic strategy for investing in an economic infrastructure that could potentially create economic conditions for growth and prosperity over the next five years among the Black population of Indianapolis, which represents roughly 30% of the total population, if that were its focus. This strategic planning process is similar to the CEDS planning followed by nearly every region’s economic development planners and policymakers across the nation. But any economic strategy that intends to increase Black productivity in Indiana must prioritize investing in a culturally competent and capable economic infrastructure designed to address the 20th century systemic challenges inherited by the current body of policymakers and economic development leaders. Even Accelerate Indy acknowledges this point:

“… concerns abound that the region and the state of Indiana as a whole is not viewed as place that is innovative or ‘culturally sophisticated.’ Although proud of the growing organizational capacity, entrepreneurs noted that this capacity and culture that it seeks to develop is highly fragmented. Focus group participants noted a distinct absence of a single organization that coordinates the regional entrepreneurship community, serves to promote entrepreneurs locally and nationally and acts as a one-stop shop for entrepreneurial services. While many focus group participants identified the Business Ownership Initiative (BOI) as an important asset for the community’s entrepreneurial culture, others found that the services it offers are “too basic” for certain sectors or particularly high growth, high risk ventures.”

“How Do We Get There From Here,” will be the focus of my discussion at the Beyond 2020 Indiana Minority Business Conference on Aug 28-29, presented by Innopower LLC and Recorder Media Group. Please join us.

Mike Green is chief strategist at The National Institute for Inclusive Competitiveness and co-founder of ScaleUp Partners, a consultancy specializing in inclusive competitiveness strategies to improve the productivity of underrepresented minorities in the innovation economy. Email mike@niicusa.org.

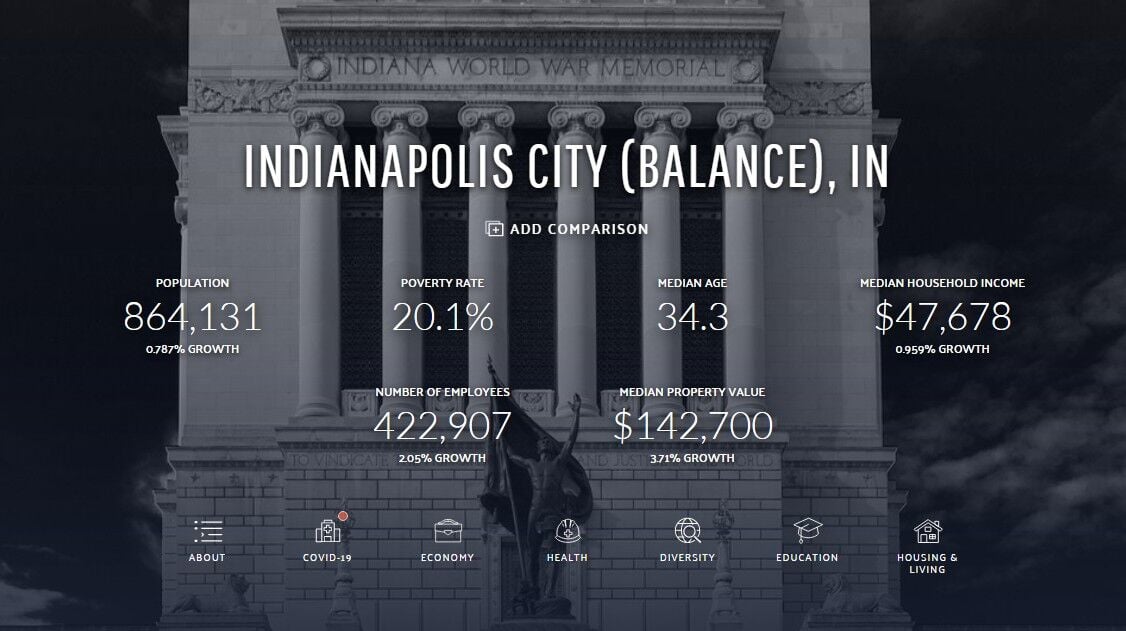

(Source: Data.io)

(Source: Data.io)

“> (Source: Data.io)