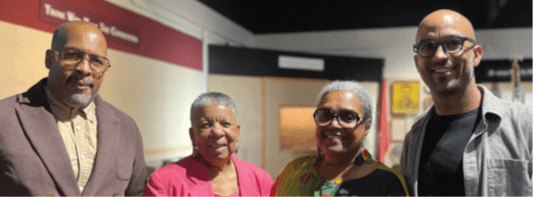

S. Smith’s descendants: Norma Johnson, Lora Henderson and Samuel

Levi Jones. (Photo/Camike Jones)

In the heart of Downtown Indianapolis, at the Crispus Attucks Museum (CAM), now stands an installation of anti-lynching art from the early 1900s. “Unmasked: The Anti-Lynching Exhibit of 1935 and Community Remembrance in Indiana” opened at CAM Aug. 11 and will remain at the museum through March 2024.

The art displayed at the exhibit reflects anti-lynching efforts that took place in the 1930s. Instead of focusing on the graphic imagery of the victims, the exhibit primarily showcases artwork that was used to oppose lynching.

“The exhibit is really organized not so much around the depiction of particular lynchings,” said Alex Lichtenstein, exhibit co-curator and professor and chair of Indiana University Bloomington’s Department of American Studies.

“The exhibit really focused on, first and foremost, trying to recreate two art shows, art exhibits that were done in the 1930s as anti-lynching protests,” Lichtenstein said. “So, it’s about how artists have tried to find ways of depicting lynching in general rather than specific lynchings in a way to highlight the atrocities to spur people to action. So, it’s really about artistic representation and social protest through art.”

The infamous picture of the lynching of Thomas Shipp and Abraham S. Smith that took place in Marion, Indiana in 1937 is featured in the exhibit. This photograph was included because of its connection to Indiana as well as its worldwide significance in the anti-lynching movement.

Those left behind

Three of Smith’s descendants, Norma Johnson, Lora Henderson and Samuel Levi Jones, were present at the opening of the art exhibit. They wanted to remind people that Smith, whose life was cut short at the age of 18, was a beloved member of their family.

“He was somebody, not just a picture,” said Johnson, who is known as the family’s historian.

“I don’t even think we have a photo of him beyond him hanging on this tree,” added Henderson, whose mother was Smith’s sister.

Smith was accused of a crime, but there was never a trial or conviction. Instead, his body was dragged, beaten and hung without evidence that he had ever committed the crime. Johnson said the family never even knew if he was guilty.

The photo of Smith and Shipp has been displayed to the public for years, but privately the family did not talk about the tragedy.

Henderson, a mental health and wellness practitioner, said living with the memory of lynchings has affected Black families for generations, leading to trans-generational trauma. The trauma comes out in behaviors that are passed down from one generation to the next.

“We generally, as Black people, as a family, have had so much trauma from slavery on up,” Henderson said. “We think not talking about it will make it go away, but it comes out in substance abuse disorder, domestic violence; various things can trigger this for you.”

Smith’s family continued to live in Marion after the tragedy occurred. Some relatives remain there to this day.

“My family was a strong family to continue to live in Marion with that last name. You had to have strength to live through that and to continue to live there,” Henderson said.

The legacy of lynchings

Rasul Mowatt, co-curator of the exhibit and department head and professor for the Department of Parks, Recreation, and Tourism Management at North Carolina State University, hopes the exhibit will inspire people to action to address the violence that is still occurring against Black people.

“It has not gone away at all. Lynchings as lynchings still exist today,” said Mowatt.

Modern lynchings can also look like other forms of violence.

“Lynching still exists. It exists in other forms in many ways, but Black people are still being violently killed,” said Phoebe Wolfskill, co-curator of the exhibit and associate professor of African American and African Diaspora Studies at Indiana University Bloomington.

Specifically, the deaths of Michael Brown and George Floyd motivated the co-curators to make sure this exhibit came to be. They recognized that the nation was beginning to come to terms with its history of racist violence.

“This is imperative that people remember that this is a long history. This isn’t one cop. This isn’t one person saying, ‘I can’t breathe.’ This is embedded in a long history and a long history of protest against this sort of action,” said Lichtenstein.

For Mowatt, the purpose of the exhibit is not just to remember the past but also to motivate people to engage and take action against such violence now.

Several IPS high school students were in attendance to view the exhibit on opening night. Dr. Aleesia Johnson, IPS superintendent, said it was important for youth to know this history so that it would never, ever happen again.

“They were human”

Inspired by the trees she saw while driving through Ohio, Dr. Mattie Lee Jones, a visual artist, was commissioned to paint two original pieces for this exhibit. Both pieces were meant to evoke a spiritual connection and to humanize the experience of the victims. For Lee Jones, it was important to remember that the victims were real people with loved ones and families.

“He was somebody’s brother, somebody’s uncle,” said Lee Jones of her painting entitled, “Reaching for Heaven I.”

Her second piece, “Reaching for Heaven II,” depicts a male and a female form within the trunk of a tree.

“I wanted to remember that there were females that were also lynched,” Lee Jones said.

Her paintings were hung next to spiritual texts, which Lee Jones felt helped to bring out the message of her art.

Henderson wants people to know the humanity behind the history of the lynching victims.

“They are loved. They were human, they really were,” Henderson said.

Because Smith’s life ended so abruptly, Henderson said it is her purpose to continue telling his story.

“I have to live for him. I have to speak for him,” Henderson said.

The Crispus Attucks Museum is located at 1140 Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. St. The museum is open Tuesday-Friday from 10 a.m.– 6 p.m. and Saturday and Sunday from 10 a.m.– 3 p.m. The museum is closed on Mondays.

Camike Jones is the Editor-in-Chief of the Indianapolis Recorder. Born and raised in Indianapolis, Jones has a lifelong commitment to advocacy and telling stories that represent the community.