The Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields has recently unveiled “Composing Color: Paintings by Alma Thomas,” a touring exhibition organized by the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s Melissa Ho, its curator of 20th century art.

Comprised of 19 works, the showing offers an overview of Thomas’ art, while highlighting her interest in nature, music and the many iterations of beauty which she surrounded herself with.

Born in 1891, Thomas was principally concerned with these passions, and received criticism from her contemporaries for her post-racial perspectives and focus on abstraction. Up until her death in 1978, she decried the notion of being called a “Black artist,” opting instead for a more direct recognition. “I’m a painter,” she’d say. Even still, Thomas’ career was an immensely important one, with her having significantly elevated people’s appreciation of Black art.

In 1972, she was the first woman to have her art exhibited in a solo show at the Whitney Museum in New York. Similarly, in 2015, her work was the first of an African American woman’s to enter the White House Collection following the Obama’s display of her painting Resurrection (1966) in the dining room of the residence.

The pieces Newfields presents, generally speaking, show a more mature part of Thomas’ artistic output. Whereas “Resurrection” sees her mosaic spiraling used to note the singularity of the infinite and the finite, matching yellow hues at the center and exterior of her work in an intuitive display of exuberance, the works in “Composing Color” are much more cognitive.

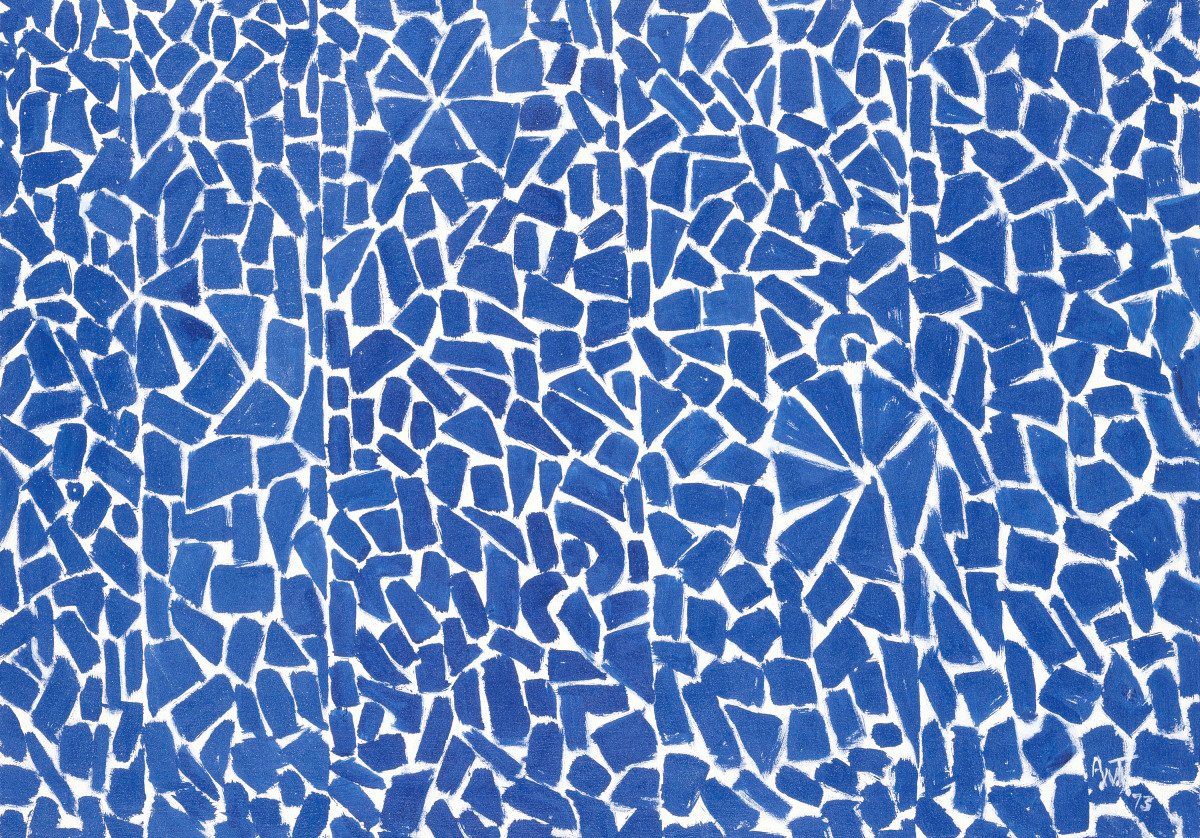

One need only look at “Elysian Fields” (1973) for a comparative example of the salvation of souls, and a display of Thomas’ increasing attentiveness. Named after a special part of the Greek afterlife which “The Odyssey” describes as being “where there is made the easiest life for mortals,” “Elysian Fields” is a paradise of paradises.

Like all utopias, it is an amalgamation of good individuals striving to be great. Thomas shows this with tact, creating a work comprised of disparate hues of blue that, when viewed in full, reflect off of each other in a pure display of color which seems to propel itself off of the wall.

The result of the unison is at once both solid and transient. In certain instances, it is as if the white background of the piece ceases to exist, but glance at just the wrong angle and you run the risk of missing the entire effect. In this way, the carefully constructed piece is not unlike the mythological imagination of utopia, at times unbelievable or hard to grasp, yet seemingly always inspiring even in its absence.

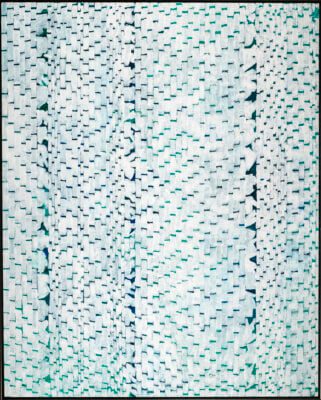

Further examples of Thomas’ commitment to the cerebral can be seen in “Untitled” (Music Series) (1978) and “Arboretum Presents White Dogwood” (1972), which see her meaningfully capture the movement of her respective subjects.

In the former, she returns to the comfort of her spirals, deconstructing their shapes while maintaining the flow of their forms, like the slight change of a chorus the second time it’s sung. Likewise, the latter work’s attention to the narrowing and thickening of its white blotches does a brilliant job replicating the dogwood tree’s layered and stacked foliage as it blows in the wind. In these works and others, she is not only painting, but delineating.

Though evidently analytical, her art also brings forth valuable insights into humanity’s relationship with the world.

Works like “The Eclipse” (1970) and “Snoopy Sees Earth Wrapped in Sunset” (1970) offer audiences an eyes-wide-open adoration that is deeply relatable, while pieces such as “Fall Begins” (1976) encapsulate subjectivity, offering a look at looking in a work that emphasizes the intangible and emotive qualities that accompany perception.

In a platonic way, with an impression firm in her mind, even completely random and expressive brushstrokes became conformed catalysts for her intricate experiments in color and light — single components of a larger experience of dynamic synergy. They are like the phantom waves of photons bent by gravity, seemingly predestined to present marvels to the eye.

Thomas once stated that Cézanne “gave an architectural structure to color,” and some have likened the French painter to a creator of distanced dreamscapes. Clearly, with her excavation of the imaginative from the mundane, she shows us all that we need not sleep to find fantastical sorts of beauty.

Caiden Cawthon is a legally blind writer who seeks to shine a light on that not readily seen, and can be found on Instagram at @caidencawthon.