This story was originally published by Chalkbeat. Sign up for their newsletters at ckbe.at/newsletters.

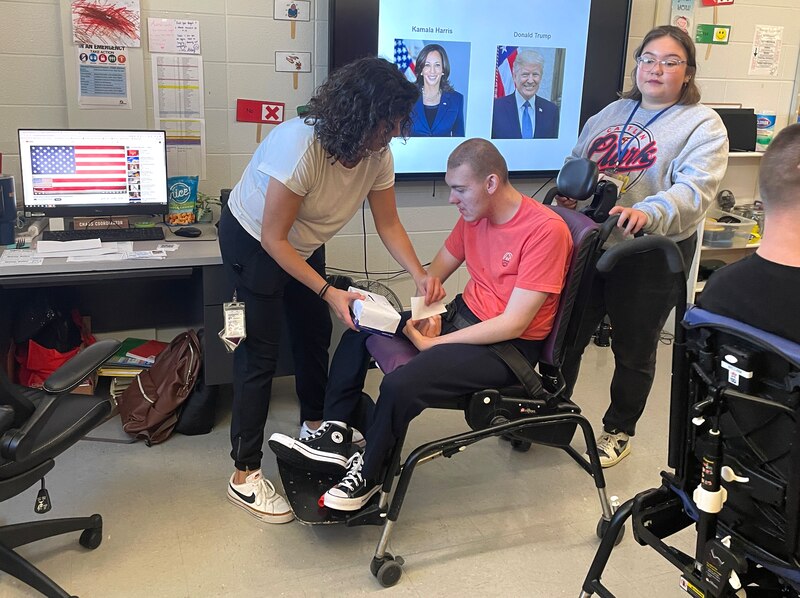

With “The Star Spangled Banner” playing, students in Monica Poncé’s class cast their vote for U.S. president in a mock election. But this democratic process had its own look and feel.

Each student sat in front of a projector screen showing portraits of the candidates. Poncé held a pair of buttons. She pressed the blue one for students to hear “I’m Kamala Harris” in the candidate’s voice. Next was the red one that said “I’m Donald Trump” in his voice. Then it was the student’s turn.

Some students made their choice by pressing the button. One touched sensory pads that corresponded to the candidates. Another indicated his choice between a plastic toy donkey and elephant. Two picked by fixing their gaze on one of the candidates on the screen.

“Thank you, that’s a good choice,” Poncé said regardless of the student’s choice. Together, they’d mark the paper ballot and put it in the cardboard ballot box.

Each of the seven students in her high school class at RISE Learning Center has physical, cognitive, and communication disorders, plus a majority of the students also need services for blind or low vision. All are nonverbal and working toward a certificate of completion instead of a diploma through the Mobility Opportunities via Education — or MOVE — program.

They’re among thousands of Indiana students participating in mock elections as their teachers use the contentious 2024 presidential election to teach the importance of voting, civic engagement, and democracy.

Some are voting for their class president, or the choice between an ice cream or pizza party. Others are studying the real-world 2024 presidential candidates, and historical examples of activism and voter suppression.

What they have in common is an emphasis on the power of a vote during a presidential election where youth engagement may play a significant role in the results.

Poncé said that because her students can’t say what they want or like, things are often done for them.

“When I can give them a choice, I want to give them that opportunity to have a say in what they are doing,” she said.

Teacher helps students with disabilities be community participants

RISE, on the southside of Indianapolis, describes itself as “a cooperative special education program.” It serves students from Beech Grove City Schools, MSD of Decatur Township, and Perry Township Schools as well as a few from schools in Johnson County.

“I teach our students to be active members in the community,” Poncé said of her students, who are ages 15 to 22. “They can be dismissed by the community for not having thoughts or opinions because they are nonverbal.”

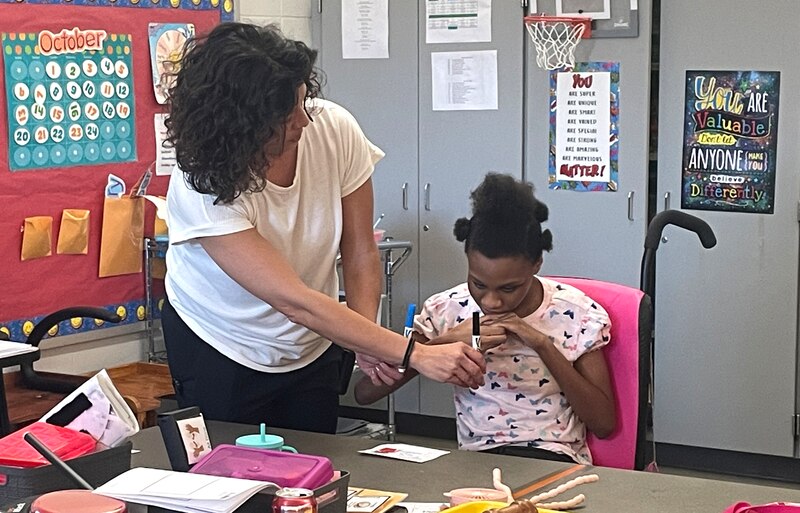

One of their electoral decisions was picking between blue and black markers to sign the mock voter registration cards they made earlier in the week.

Voter registration is a formal document, and formal documents are completed in blue or black ink, Poncé told them, as she and the instructional assistants held up markers to each student.

Earlier in the lesson, Poncé reviewed the “w-h words” of the presidential election with the students: what, when and who. She included the colors and symbols of the political parties too.

Poncé told them that they would wait their turns to vote because sometimes the lines at a polling place are long. And the results take time, she said, so they wouldn’t know until later in the day who won the class election.

Two of the students are old enough to actually vote. Poncé said that when her students turn 18, one of several resources she shares with families and caregivers is information about registering to vote and where polling locations are.

“We get to make a choice of who we want to run the country,” she told the class.

A school studies voter participation and activism

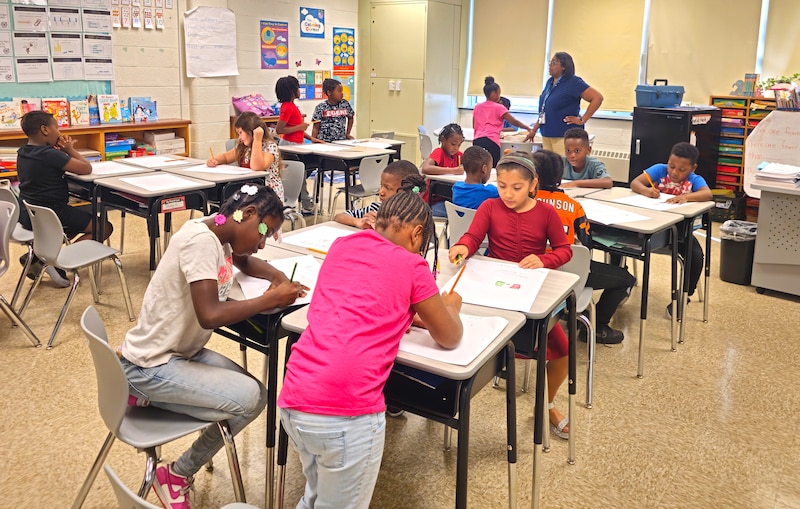

At Sankofa School of Success, an Innovation Network school in Indianapolis Public Schools , Treasure Jones’ first graders came up with the qualities they want to see in the next school president.

Someone who uses kind words and actions. Someone who’s hard working, helpful, and happy.

Then they gathered around Jones as she read aloud from a book called “V is for Voting.” She reminds them of an earlier lesson about voter suppression — they agreed it would not be fair if Ms. Jones stopped someone from voting in the school election just because they have bad grades, for example.

“What’s a campaign?” one student asked in the middle of the book.

“It’s all the things you do to convince people to vote for you,” Jones said.

Jones also reminded them of why voting is important to her: “It’s important to me that potholes are filled. It’s important to me because I love to teach you guys that you have safe schools.”

She also told her class about why she votes and attends school board meetings.

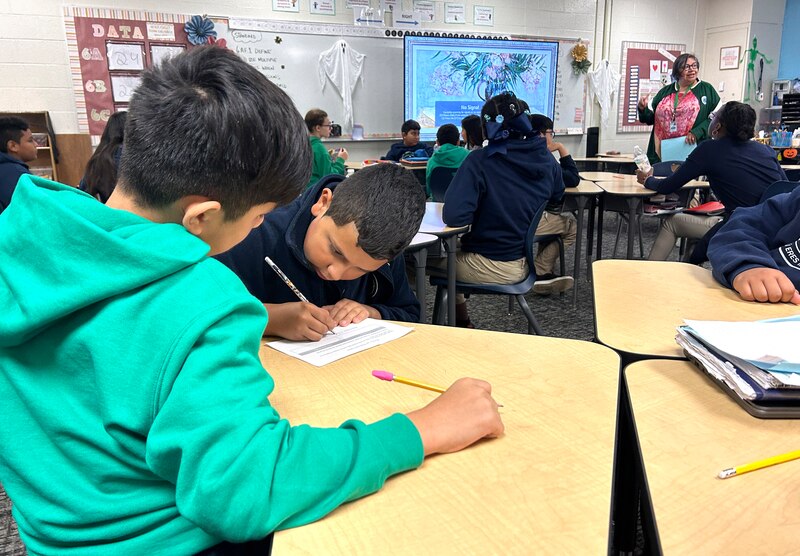

At Sankofa, a K-6 school in the Martindale-Brightwood neighborhood, voting is a school-wide, month-long project, with different lessons at each grade level exploring voter participation, activism, and more. A mock election on Nov. 5 — with fifth graders running for office and sixth graders acting as the electoral college — caps the project.

There are real-world connections, too, as students will also cast a vote for the presidential candidates in a mock election.

“The littles bring a different energy to it,” said Eldridge Chism, the assistant head of school.

In Danita Logwood’s second grade class, students are designing posters specifically to urge their parents and older siblings to vote. Without voting, you lose out on your chance to make change and influence how things are done, Logwood said.

Here’s how she put it to the second graders: If the class has recess out on the playground, but you wanted to go to the courtyard, you might feel upset, but did you put up your hand and vote when you had the chance?

Logwood stressed the importance of voting in another exercise: She described the voting requirements in different periods of U.S. history, then asked students to stand up if they matched the requirements. At the beginning, only white male landowners could vote — so no one in the class could stand.

Fifth grade teacher Ashley Helman said the idea for the mock election originated with the students themselves, who would hear about the presidential election at home and then come into class and ask questions. Often, those questions were who the teachers themselves would vote for.

Helman told them that no, they can’t share those opinions as teachers. They should ask their parents.

“What I can do is let you know about the process and how it works,” Helman said.

How will Americans feel after Election Day?

At Enlace Academy, another Innovation Network school within IPS, sixth grader William Ulin took his defeat with grace.

He and a table of his classmates represented the state of Florida in a lesson on the Electoral College just 12 days before Election Day. The choices: an ice cream party versus a pizza party.

As a hypothetical Florida resident, William voted for pizza. But his fellow classmates swung the state in favor of ice cream. Ultimately, the classroom — the entire nation — made ice cream the winner.

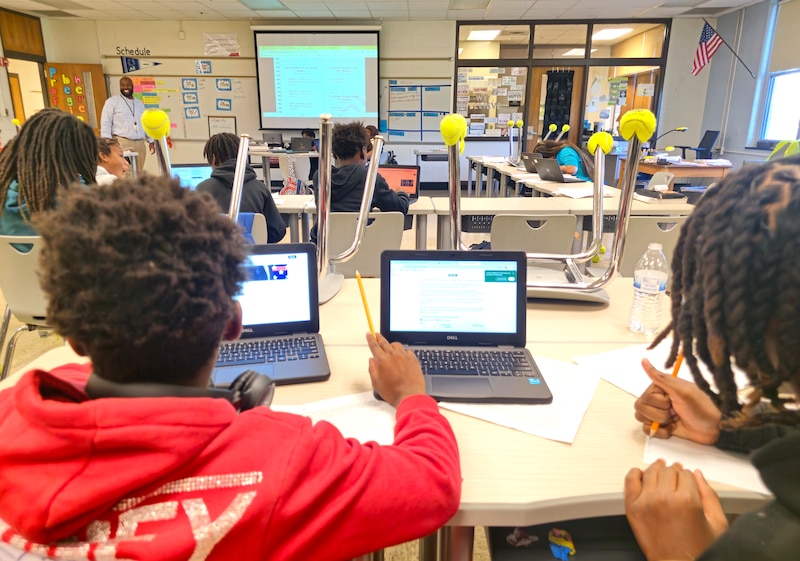

The activity was the latest in a series of lessons on the election process that the K-8 school in the International Marketplace neighborhood on the city’s west side planned throughout October for its middle school students.

The lessons — taught during the school’s weekly “community meetings” that help build community and character — align with the school’s core values of citizenship and integrity. Students have learned about political mudslinging and how to spot reliable sources of news.

In an open-house event two weeks before Election Day, eighth graders also gave presentations on issues important to them and researched how both presidential candidates would impact the topic.

As sixth grade math teacher Elise Correa counted up the electoral votes for ice cream and pizza, School Leader Stephanie Campos reflected with students.

“How do you think Americans are going to feel after Election Day?” she said. “Someone’s going to be upset, right?”

Campos asked students how they would respond if their chosen candidate lost. Madeline Corado pondered the question.

“Be happy for them?” she asked.

“There’s only so much you can control, right?” Campos said. “But you can just keep on moving.”

Aleksandra Appleton covers Indiana education policy and writes about K-12 schools across the state. Contact her at aappleton@chalkbeat.org.

Amelia Pak-Harvey covers Indianapolis and Marion County schools for Chalkbeat Indiana. Contact Amelia at apak-harvey@chalkbeat.org.

MJ Slaby oversees Chalkbeat Indiana’s coverage as bureau chief. Contact MJ at mslaby@chalkbeat.org.