A black entrepreneur’s “power move” on the energy sector could create hundreds of jobs in one of the the poorest communities in Texas.

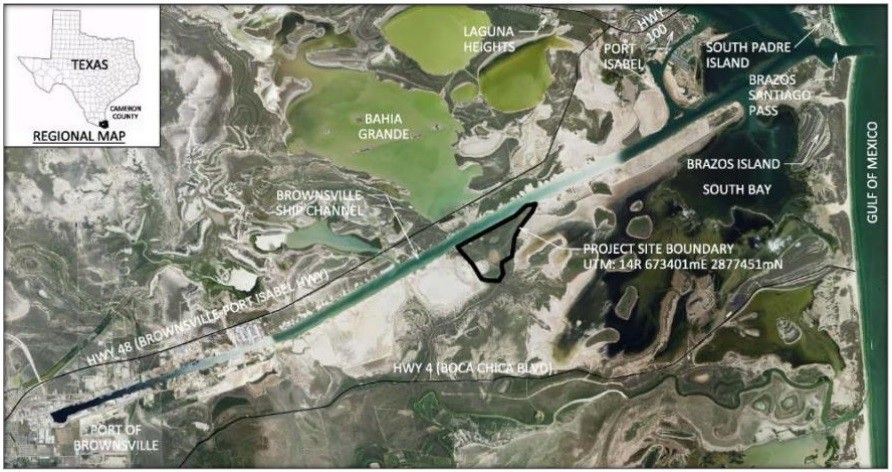

Houston-based businessman Phillip Franshaw is building Annova LNG, a multi-billion-dollar liquefied natural gas export facility on the Brownsville Ship Channel along the Texas Gulf Coast. If successful, the project could support more than 650 construction-related jobs and another 165 permanent jobs once completed, at an average salary of $70,000 a year or more.

Franshaw is gambling on a process called “liquefaction.” It supercools and converts natural gas into a liquid and makes it easier to transport via tanker to utilities and other major consumers in Asia and Europe. This technology requires the construction of an approximately $3 billion plant, a massive undertaking on many levels.

This project has been years in the making.

Annova LNG was born as a two-man shop, when president and founder David Chung asked Franshaw to help finance the facility. Chung coined “Annova,” a twist on the word “innovate.”

The duo took the project to market and soon began collaborating with Exelon Corporation, a major US utility and operator of America’s largest fleet of nuclear power stations. Exelon purchased a controlling interest in Annova in July 2014 and maintained Franshaw’s management team.

“Having a quality sponsor of that magnitude has given us the leverage to aggressively approach the market and execute through the development phase of the project in a most effective way,” Franshaw said.

Yet, Annova faces stiff competition. At least 50 companies have applied for federal permits to export domestically produced liquefied natural gas. Two other plants are headed for the Brownsville Ship Channel.

Annova distinguishes itself from these other ventures, however, by building a facility that can offer buyers more flexibility, Franshaw said. This approach decreases construction costs, limits risk, and can be scaled up if demand eventually grows. “We think the future of the market will be small-scale facilities, and that’s how we differentiate ourselves,” he said.

Once running, Annova could yield state and local tax revenue exceeding $60 million annually. More than half of those funds would support local governments in Cameron County, the southernmost in Texas. Those $30 million could pay the starting wages for about 698 teachers, 850 cops, or 1,029 firefighters every year, according to SalaryGenius.com.

Franshaw’s enthusiasm and determination are evident when he speaks about the project and describes the values that have helped him succeed in business. “We all face a range of different challenges throughout our careers,” the Georgetown University graduate said. “I think, fundamentally, one of the biggest challenges we face is credibility. Who are you? People want to know that.”

“Often kids go to school and get a great education thinking that’s enough for them to sit in the captain’s chair and start making decisions,” Franshaw said. “But everyone’s expected to pay their dues and learn the industry while developing a voice as well as credibility. It’s on that basis that people begin to trust you. Your track record is critical. It’s important that you buckle in, plan to pay your dues and grow.”

Franshaw travels extensively, to recruit customers. In fact, he spoke with Urban News Service right after a business trip to Asia, where he huddled with potential buyers.

“Anyone who knows me knows that when I commit to a project, I’m all in,” said Franshaw. He also attributes his success to the team as a whole. “My outside interests largely rest with my family. I have three children, and I just hope that I’m working at a pace and with the appropriate level of integrity to serve as an example of the quality of men that I would like them to grow to become.” He and his wife, Maria, affectionately calls their sons Trouble 1, Trouble 2 and Chaos. They study, respectively, at Rice University, University of Texas and a Houston high school. Chaos aspires to Annapolis.

“I’m currently traveling approximately 75 percent of the time,” Franshaw said. “I’m out at least three weeks of every month, and my wife really anchors our family. Without her, I couldn’t do what I do.”

Annova plans to have its first stage operational by 2020.

One key hurdle is obtaining approvals from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission.

After reviewing Annova’s initial 1,670-page application, the commission will spend at least one year reviewing a more detailed filing before it authorizes construction.

While liquefied natural gas sales have climbed recently, the market five years from now is expected to be quite different. “There currently appears to be a glut of LNG in the market, and we think that while there is an oversupply now, much of that will be absorbed by 2020,” Franshaw said.

Annova faces stiff competition. At least 50 companies have applied for federal permits to export domestically produced liquefied natural gas. Two other plants are headed for the Brownsville Ship Channel.

Annova faces stiff competition. At least 50 companies have applied for federal permits to export domestically produced liquefied natural gas. Two other plants are headed for the Brownsville Ship Channel.

“> Annova faces stiff competition. At least 50 companies have applied for federal permits to export domestically produced liquefied natural gas. Two other plants are headed for the Brownsville Ship Channel.