At the Malcolm X Institute of Black Studies on the campus of Wabash College, legacy lives and breathes.

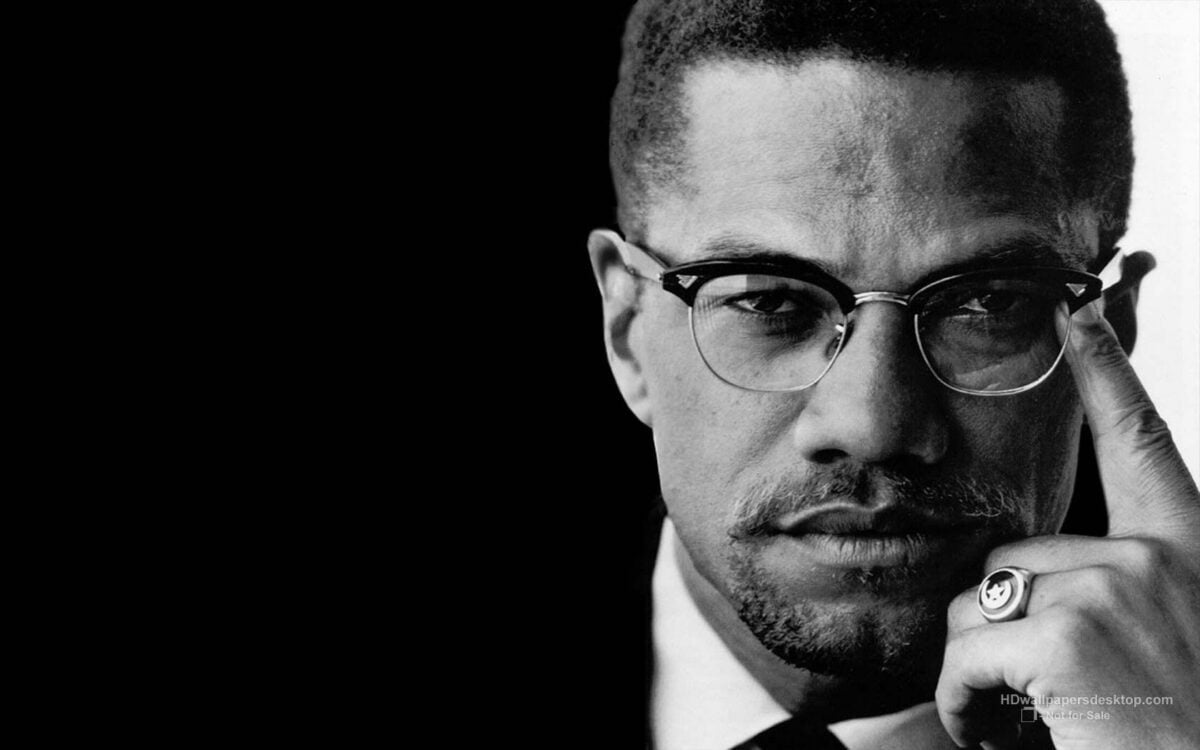

This year, as the institute marks its 55th anniversary, Ilyasah Shabazz, daughter of Malcolm X and Betty Shabazz, visited the small liberal arts campus to reflect on her father’s life and the movement he helped ignite.

With Malcolm X set to turn 100 this May, Shabazz continues to preserve and amplify his message through her writing, lectures and community work. During our conversation, she spoke candidly about his enduring influence, the power of identity and what it means to carry forward a legacy rooted in justice and self-determination.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Hanna Rauworth: Growing up the daughter of Malcolm X, how did your father’s influence shape your own views on race, identity and activism?

Shabazz: My mother raised us like in a bubble of love, and I perceived that we were all a family of God … During the summer, I would go to camp with my younger sister in Vermont. It was based on the principles of Quakers and the indigenous Native American values. We learned about farming, fishing, swimming, archery, horseback riding, etc. and learned how to live off the earth and how to cohabitate with God’s creation.

I remember it wasn’t until I saw Roots that I said, ‘Whoa.’ I remember going back to camp and looking around and seeing that there were no Black boys in our neighboring camp. I didn’t really want to go back to camp anymore after that … My mother raised her children within this bubble of love, and so we didn’t differentiate between races and all that stuff.

Rauworth: When you say you didn’t want to go back to camp anywhere, can you explain why?

Shabazz: I was 15. I was becoming a young adult, and I wanted to see boys … It was just a very interesting time in my life. You can imagine by the time I went to college; I was going to camp in Vermont, I had gone to the all-girls prep school, and I really wanted to go to school with Black people.

I know my mother was probably a little fearful because I was very naïve, and so when I went to college, they heard Malcolm X’s daughter was coming to the university, and they had already decided the dorm that I was going to live in, and they decided that I was going to be the chairperson of the Black Student Union. When I got there, it was like a disappointment because they and the world had been misinformed about who Malcolm X was.

For me to be like, ‘Hey guys, you know, just say no to drugs, love, peace, joy, say no to teenage pregnancy,’ they were like, ‘Whoa.’ They were expecting someone to be really fiery and angry. In order to take on such a responsibility and have such a profound reaction to injustice in the manner that (Malcolm X) did, you have to have been a person of love, peace, joy, righteousness and equality.

Rauworth: So, people were expecting you to fight hate with hate, but you were pushing for peace and love?

Shabazz: Yeah, because they didn’t see the hate that was in slavery. The hate that created racism, sexism, genderism. They didn’t see that hate.

They just thought Malcolm would filter hate, and Malcolm was the one who said, ‘Don’t put that onus on me. I didn’t create racism. I didn’t create sexism. I didn’t create these things. I have a profound reaction to it.’ He said, ‘If you stick a knife in my back nine inches and you pull it out six inches, the knife is still in my back. If you pull it all the way out, that’s not progress. Progress is coming to the table together and addressing the wounds that the blow made,’ and that’s what he wanted … There’s enough for everyone, right? There’s no reason to bomb a community or country. For what reason?

I remember when I went to South Africa with President Clinton as part of his delegation. First, I was so surprised to see that South Africa was a beautiful establishment … I remember being in church, and I turned and looked at everything, and there were these young girls, and we connected. I turned, and I would wave and continue watching the service, and I would turn around, and they would wave back, and it was like an innocent connection. I was so hot, so (the other individuals on the delegation) put me in (a cool spot) to cool off …

When it was time to go, there were three girls, and they said they would not leave because they wanted to make sure that the woman in the blue dress was okay. I had to think about it because how many people did they see taken away and never returned? They didn’t know where these white men escorted me and that I was a part of this presidential delegation … I went out to say hi and we smiled and hugged. Then I got back on the bus and said goodbye. We went to the airport. We got on Air Force One and I just couldn’t stop crying. I was crying because I made a connection with these girls that I’d never see again.

Rauworth: Do you think your mother made the right decision to raise you in that bubble?

Shabazz: I think she did. I respect how she raised us because she was only in her 20s when she saw her husband gunned down. That had to have been a lot of trauma … She wanted to make sure that she protected us from the pain that she felt, and her best way of doing it was making sure that we knew that we were worthy of love and all these things.

Rauworth: Your father spoke openly about the psychological toll of racism and oppression. How do you view the relationship between mental health and activism in the Black community today? What steps are being taken to address those mental health needs?

Shabazz: For so long we were told (the way we looked) was bad, and so for people to now protest and say, ‘I’m great. I’m beautiful. Look at me. Black excellence,’ It’s great, and I know that sometimes it’s also alienating … I have a lot of white friends, and I know when I make all these posts about all of the injustice that’s happening to children, to communities, to elders, that I know that it alienates some of my white friends.

Rauworth: How do you think activism has evolved with the rise of social media and how do you use these tools in your own work?

Shabazz: I remember my sister a year ago. I would ask her a question, and she would immediately go to social media to get the answer. I was like, ‘What in the heck is this?’ Now I understand that it is a place to get lots of information, and I think, as long as we’re getting educated properly with the right information, it certainly is an effective teaching tool.

Rauworth: How do you define your mission, and how do you carry forward your father’s legacy in your work with activism?

Shabazz: It’s a way of life because even when we look at my father, I don’t think we would say he was an activist. But he was if we’re looking at the way it’s labeled today. I think that my father was genuinely concerned about the welfare of human beings because, as I said, we were raised to believe that we were all children under the fatherhood of God … If I don’t learn to love myself, then I can’t see you as a reflection of me.

And I will never love you because I don’t know how … It was my father’s commitment to God that enabled him to speak truth to power and that enabled him to see rights and wrongs.

To learn more about the Malcolm X Institute, visit Wabash.edu/mxibs.

To read more like this, click here.

Contact Health & Environmental Reporter Hanna Rauworth at 317-762-7854 or follow her on Instagram at @hanna.rauworth.

Hanna Rauworth is the Health & Environmental Reporter for the Indianapolis Recorder Newspaper, where she covers topics at the intersection of public health, environmental issues, and community impact. With a commitment to storytelling that informs and empowers, she strives to highlight the challenges and solutions shaping the well-being of Indianapolis residents.

This is such a useful article—thanks for putting this together!