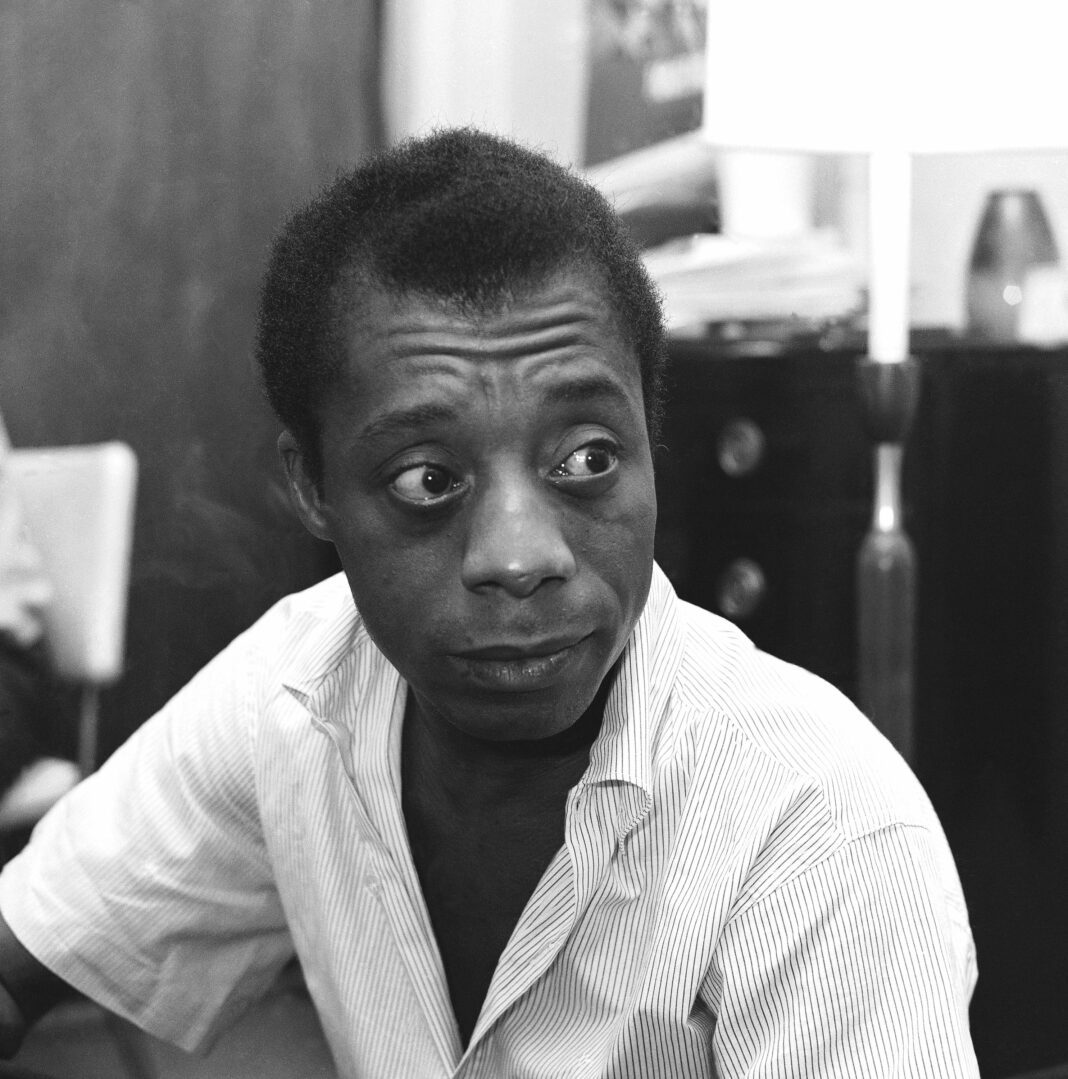

The Recorder honors James’ Baldwin for the centennium of his birth

Writer Guy Hayes sat down with one of the Recorder’s regular contributors, Larry Smith, to discuss the 100th anniversary of James Baldwin’s birth.

Guy Hayes: Aug. 2 of this year marked James Baldwin’s 100th birthday. Over the span of this centennial period, we have seen many changes in social and cultural issues, as well as in relations across and within racial and gender lines. What do you think about that?

Larry Smith: It seems almost trite and lazy to refer to James Baldwin as a “genius,” but you’re absolutely correct to do so because that’s exactly what he was. We throw that word around in such a willy-nilly way, which has robbed it of much of its efficacy. However, to the extent that it still means something — and it does — James Baldwin was a genius.

Of course, he was a genius who battled multiple demons. Some of those demons came from within, whereas others were thrust upon him. The primary ones had to do with his three most important identities: a Black man, a gay man, a writer. Baldwin never rejected his Blackness, but he had a fraught relationship with race throughout his life, primarily because of his interactions with white people — both in America and abroad. Needless to say, he also had his fair share of challenges from other Black people, especially those who were wealthy — and especially those who were light-skinned.

Interestingly, Bessie Smith, who Baldwin never met, helped him to come to terms with his race. He almost involuntarily came to listen to her music, endlessly playing her records while he was writing his first novel, “Go Tell It on the Mountain,” in Switzerland. The brilliant, and troubled, blues singer acted not only as his muse; she helped him to stop running from what he referred to as “shame.” He was ashamed of many things. His father. How he (Baldwin) spoke as a child. He was even ashamed of eating watermelon because of the racial stereotype that was associated with it.

In Baldwin’s words, Smith helped him to “reconcile (himself) to being a nigger.” Prior to then, Baldwin frequently engaged in what we now call “code-switching.” He went to great lengths to change how he spoke, especially around white people. He told Studs Terkel:

“… one of the great psychological hazards, of being an American Negro. In fact, much more than that. I’ve seen a great many people go under because of this dilemma. Every Negro in America is in one way or another menaced by it. One is born in white country, a white Protestant Puritan country, where one was once a slave, where all standards and all the images … when you open your eyes on the world, everything you see: none of it applies to you.”

Hayes: I believe Baldwin’s great strength was clarification of ideas time and again in different contexts and under different auspices. What do you think is his strength and uniqueness as an artist and writer?

Smith: Baldwin was such an astute observer of American society, especially as regards racial issues. He often referred to himself as a “witness,” in the sense that Black folks use this term in a religious context. His frequent travels outside of the U.S. helped him to understand his homeland more acutely, which is a common phenomenon. Indeed, he confessed that he could never have “forgiven” America had he not traveled outside of it.

Baldwin had his proverbial finger on the pulse of the vicissitudes that shape our racial reality — in his lifetime and beyond. For example, something else that Baldwin told Terkel was quite prescient, so much so that it easily applies to white people’s fears regarding the ascension of President Obama:

“No matter who (white) Southerners, and whites in the rest of the nation, too, deny it, or what kind of rationalizations they cover it up with, they know the crimes they have committed against black people. And they are terrified that these crimes will be committed against them.”

Hayes: Was there anything in the interview that reminded you of his humanity, his future view, his professional self-image?

Smith: Yes. Baldwin was all too human. For example, his relationship with his sexuality is quite complicated. While he was an “out” gay man for nearly his entire adult life, he never was comfortable with that particular term. In fact, he said that he didn’t even know what it meant. Further, he was very clear that racism was quite prevalent among white gays; the fact that they shared a sexual orientation with bay Blacks did not necessarily mean that they were more racially enlightened.

In general, Baldwin actively eschewed labels — except that of being a writer. He was even uncomfortable being referred to as a “Black writer” because he felt that it pigeonholed him. Indeed, he believed that writers — Black and white — could somehow transcend the concept of race by being true to themselves. At least, that’s what he argued; it’s difficult for me to believe that he actually believed that. I think that he was being aspirational.

Interestingly, when asked whether he ever considered having children as a gay man, Baldwin reflected that his professional life was too complicated as a younger writer. He then said that, in mid-life, it was too late. Astoundingly, he made no comment about the overwhelming legal hurdles that he would have faced at the time. Still, even as someone who would never be a parent, he intrinsically understood the depth of that responsibility:

“There are two things we have to do — love each other and raise our children. We have to do that! The alternative, for me, would be suicide.”

Hayes: Finally, what of being a writer? How did it suit him? Was that his “calling” — his most cherished identity?

Smith: Obviously, Baldwin is one of the greatest writers of the 20th century — if not the greatest. “Writer” is the identity with which he seemed most comfortable. As a public intellectual, he had many opinions regarding how tragic American society could be. He had many criticisms. Most of them hit the mark. For example, he said,

“One of the reasons, for example, I think that our youth is so badly educated — and it is conceivably badly educated — is because education demands a certain daring, a certain independence of mind. You have to teach some people to think; and in order to teach some people to think, you have to teach them to think about everything. There mustn’t be something they cannot think about. If there is one thing they cannot think about, very shortly they can’t think about anything.”

Further, though writing made Baldwin famous, he had a “hate-hate” relationship with celebrity. He seemed to genuinely be uncomfortable with it, believing that it robbed him of something essential about himself. For him, celebrity created an aesthetic distance from himself — and from others — which frustrated him. As I stated earlier, it was extremely important for him to be a “witness,” which essentially meant being an integrous, autonomous, “free” person. Celebrity interfered with this impulse.

Embracing one’s identity can be such an elusive pursuit, especially given that most identities are socially constructed. This means that they are malleable, frustrating, damning, and liberating — all at the same time. When asked who he was at a certain point in his life, Baldwin replied:

“Who, indeed. Well, I may be able to tell you who I am, but I am also discovering who I am not. I want to be an honest man. And I want to be a good writer. I don’t know if one ever gets to be what one wants to be. You just have to play it by ear, and … pray for rain.”

Baldwin was enigmatic. He was mercurial. He was inveterately polite. He could be frustratingly evasive. Perhaps most importantly, Baldwin spent so much of his life seeking acceptance from others. Hopefully, he eventually accepted himself.