Like other members of his family, Ralph Jefferson III heard the soft rumblings of Purdue University possibly honoring his late mother and aunt, who in the 1940s became the faces of a campaign to integrate student housing.

Jefferson wasn’t naive, though. He understood it usually takes big money to do something special, and the family wouldn’t be able to pull that off. He thought they might get a plaque or something like that.

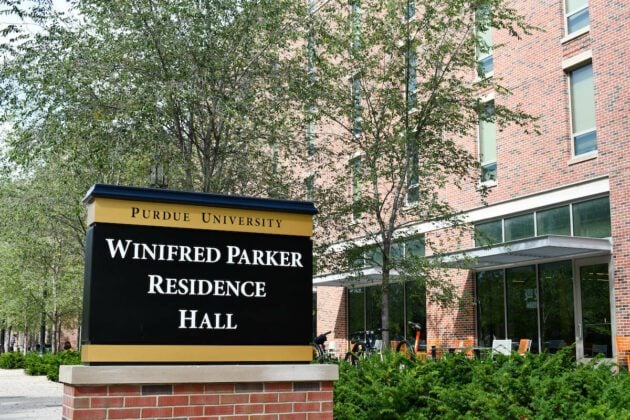

Instead, in 2021, the university honored the sisters’ legacy by renaming the Griffin Residence Hall buildings as Frieda Parker Hall and Winifred Parker Hall. They were the first buildings on campus to be named after Black alumnae.

Jefferson described his mother, Frieda Parker Jefferson, as a reserved person who didn’t like making a big deal out of anything.

Winifred Neisser, the daughter of Winifred Parker White, described her mother in the same way.

It’s not a surprise the sisters were similar in that way. They were inseparable throughout their lives; the family calculated they spent fewer than five years living more than about three miles from each other.

The Parker sisters also had to bond through an integration effort that made it all the way to the governor. Their father, Frederick, started a letter-writing campaign after Purdue initially denied the girls’ applications to live in university housing, forcing them instead to a boarding house in Lafayette.

Indiana’s governor, Ralph Gates, was one recipient of Frederick’s letters, and he agreed to take up the family’s cause.

Purdue admitted the sisters into the Bunker Hill residence halls, putting them among the dorm’s first Black residents.

The formal recommendation to name the buildings after the Parker sisters came from Renee Thomas, who’s been at the university for more than 30 years and is currently director of the Black Cultural Center.

“How fitting it would be to name a residence hall in their honor,” Thomas said.

The Parker Hall buildings are adjacent to the Black Cultural Center and close to the residence halls where the sisters lived as students.

Integrating housing at a major university seems like a good topic of conversation at the dinner table, but Neisser said her mother and aunt never talked about it as some groundbreaking moment in history.

“It was just a family story,” she said. “They didn’t make a big deal out of it.”

Neisser said integration stories tend to focus on what it meant for white people at the time, especially in a situation like what the sisters faced, where many white students in the dorm probably never had any meaningful, positive interactions with Black people. But it was the same way for White and Jefferson, who grew up in a segregated Indianapolis neighborhood and went to the segregated Crispus Attucks High School.

From what White did talk about, Neisser remembers her mother thinking white students just weren’t interested in her. In retrospect, White would later say there were probably students who wanted a closer relationship, but she didn’t recognize it at the time.

Neither of the sisters lived to see the dedication. White died in 2003, and Jefferson died in 2020, but it’s not difficult to imagine the ceremony would have meant more to them because of the educational attainment it marked rather than anything such an honor said about them individually.

Their father came from a poor family but made it to Amherst College, where he played football and ran track. He wanted that experience for his daughters and everyone else in his family, Neisser said, and the tribute at Purdue can be seen as an extension of that legacy.

But it was also about more than simply education. The Parker sisters helped change the culture at a major institution.

“They had a strong sense of what was right and wrong,” Neisser said, “and they really did believe in standing up for yourself.”

Contact staff writer Tyler Fenwick at 317-762-7853 or email at tylerf@indyrecorder.com. Follow him on Twitter @Ty_Fenwick.