Daymond Mason remembers stealing Indianapolis Recorder newspapers off his neighbors’ porches with his cousin when he was 11 years old, almost forty years ago.

He grew up in the Martindale-Brightwood area and would stand on the corner of 30th and Keystone reselling those same newspapers to community members for a dime and two nickels.

It would be one dime and one nickel if he and his cousin liked you enough.

RELATED: Living Black history, every week

“Then, one day, this man came up to us who said he worked at the paper right around the corner. We thought we were going to get in trouble, but he offered us a job as paper boys. He paid us to do what we were already doing, except we had to stop stealing the papers,” said Mason.

“I think his name was Mr. Trotter. He gave me my first job. He’d give us the papers to sell, and over time, he drove us around through the different neighborhoods to drop the papers off. It was really a staple for everybody in the community.”

The Indianapolis Recorder

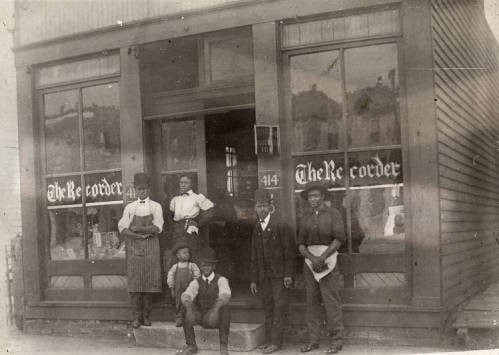

In 1897, Indianapolis Recorder co-founders, George P. Stewart and William Porter, decided to expand their already successful newssheet into a weekly newspaper.

The earliest existing issues of the Recorder date back to 1899—the year Porter sold his share of the newspaper to Stewart.

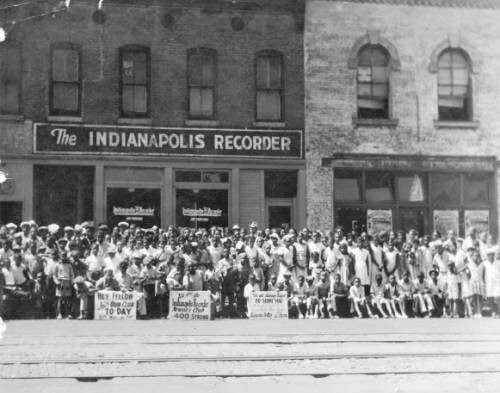

With its emphasis on local and national news, the Recorder set itself apart from other Black newspapers. It had an immediate and enduring impact on the Indianapolis community and beyond.

During the first two decades of the 20th century, through news stories and editorials, the Recorder covered the socioeconomic and political climate that affected the daily lives of its community.

The newspaper advocated for American support of World War I, assuming Black participation would bring better jobs and a better quality of life for patriots and their families.

Instead, the end of the war brought an escalation of lynchings and race riots and the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan. The Recorder devoted much of its ink to stories reporting these issues and Civil Rights Movement activities.

The Indianapolis Recorder through history

By 1987, Eunice Trotter, a journalist for the Indianapolis Star, bought the weekly newspaper. She brought in a new management style, computers and organized the paper into four separate color sections.

“I think that was my brother-in-law who helped those young men be paper boys back in the day. He worked with me at the Recorder,” said Trotter.

“I was a teenager when I started working for the Recorder. At the time, the Recorder was still located on Indiana Avenue. So, I would go there after school and run errands, or write obituaries, or do whatever I could do to learn about the business.”

Trotter said she always had a hand in the Recorder. The original owners, the Stewart family, and her family come from the same Indiana city; some of her family members married members of the Stewart family. Marcus C. Stewart, editor at the time, gave her away when she got married.

Trotter remembers working with the Black Press of America (NNPA) and pushing an advertisement campaign in the paper during her time there.

It showcased a list of local businesses that refused to advertise in the Black newspaper but received a lot of business from Black people and vice versa, with local businesses that supported the Black community.

A staple in the community

“It struck a chord with a lot of folks. There was a grocery store owner who was on the wrong side of the page. He did not return anything to the Black community, just took, took, took, and oh, he was mad,” said Trotter.

“He told me he was never going to advertise in the paper if we didn’t take his business off of that list. I told him, no sweat off my brow. It wasn’t anything that he wasn’t already doing. Eventually, he came around.”

Trotter is proud of her vision for the paper and that through the years it has fostered dynamic journalists who keep the watchdog mentality alive.

“My family needed more from me because, as you can imagine, running a paper as a woman in those times could take up a lot of your time. I had so many offers from people to buy the Recorder, but I had to give it to Bill …because he was a Black man,” said Trotter.

In 1990, William G. Mays, owner of Mays Chemical Co., purchased the Indianapolis Recorder. In 1993, the Journalism and Writing Seminars (JAWS) program was developed, allowing high school students the opportunity to receive hands-on training in journalism.

Looking towards the future

Charles Blair became president of the Recorder under Mays’ management. He remembers creating a city and county all-star basketball game put on by the Indianapolis Recorder.

“It was in 1992 or ‘93. We would take these city kids and these county kids and give them a platform to play because they didn’t have those type of opportunities. The Recorder was about community,” said Blair.

“We need to keep it going because it’s an important institution. It recorded the important stories of Black people. I took a pay cut to take the job because it was and still is so important to continue on.”

In 1998, Mays’ niece, Carolene Mays, took leadership in her roles as publisher and general manager, with the challenge to give new direction and further elevate the publication for survival and success in the new millennium.

Contact staff writer Jade Jackson at (317) 762-7853 or by email JadeJ@IndyRecorder.com. Follow her on Twitter @IAMJADEJACKSON.