By PRIA MAHADEVAN

Cecelia Dodson moved to northeast Indianapolis in 1966. The community she remembers is very different from what it looks like today.

“This was a very, very well established neighborhood with both husbands and wives working,” Dodson said, recalling the industrial plants like Ford and Western Electric that employed local residents. Dodson remembers it was a place with strong neighborhood associations, where children grew up attending local schools and moving on to college.

“There were two or three stores within walking distance of wherever you were. Grocery stores — all the amenities, cleaners, drugstores, everything in the neighborhood,” she said.

Then, in the 1980s and 1990s, industrial giants moved out one by one, taking the jobs with them. The area’s middle class has since fallen out. While the suburbs gained high-paying jobs, most growth in the city came from lower-paying jobs.

“All of a sudden we’re sitting here with nothing,” Dodson said. “That has been a disaster for this area.”

Overall, from 2004 to 2013, job growth in northeast Indianapolis was negative — at -7.4 percent.

Today, the ramifications of those decades of disinvestment are clear. According to IUPUI’s Polis Center, the poverty rate is 24 percent, with a 12 percent eviction rate. (The Marion County eviction rate is 7 percent.) Close to one in five households don’t have access to a car, and nearly half of the population does not receive sufficient sleep.

And disinvestment creates a vicious cycle.

“All you hear is the crime — you hear about the crime, but no one ever talks about the nice things that happened over here in this area,” Dodson said. “So you get that reputation, and then no one wants to do anything. […] It seemed there for a while, nobody really cared. I mean, no one was trying to bring anything to this area.”

But that may be slowly changing, with the help of a new business initiative. Following a growing national trend, Bloomington-based medical devices company Cook Medical and Goodwill of Central and Southern Indiana partnered to select a neighborhood with high economic need to house a new manufacturing facility. The goal, in part, is to counter the neighborhood disinvestment that Dodson and so many others mourn.

The partnership aims to employ people who live there, providing free education and wraparound services, and establish more higher paying jobs in the neighborhood.

Cook Medical CEO Pete Yonkman said this can create opportunities for long-term change.

“We wanted to find a lot and some land where we were very connected to housing, where people live, so maybe people are walking to work,” Yonkman said. “We didn’t want people just kind of driving in and leaving — we really wanted this to be a place where people could work for a long time.”

Other companies in Indiana that have taken this neighborhood-based approach include Cummins, Inc. and Bank of America Indianapolis, which have established targeted expansions to their operations and volunteer programs into low-income areas of the city.

And on a national level, intentional partnerships between local hospital systems and poor neighborhoods have garnered media attention.

It is a long game, but Mark Muro, senior fellow at the Brookings Institution’s Metropolitan Policy Program, says research indicates the approach can work.

“This is emerging as something that is being discussed in the business management world,” Muro said, “I think that going forward, the country and consumers are beginning to demand this from these brands.”

How it works

When it opens in early 2022, Cook Medical’s new facility will bring 100 new manufacturing jobs to the area. The company will partner with Goodwill to provide wraparound services like childcare, housing, education, and other needs that support employment and growth. Salaries will start at $15/hour.

While those salaries won’t put all employees above the Brookings Institution’s threshold for regionally-adjusted “good jobs,” the lowest salaries are more than double the state’s minimum wage. And employer-sponsored benefits include 401k matching, healthcare, and access to free educational programs — to earn high school diplomas, bachelor’s or master’s degrees.

So far, Cook Medical has subcontracted exclusively minority-owned businesses to build the site, with 97 percent of those being nonwhite business owners. (The other 3 percent are women- or veteran-owned.)

They also plan to hire between 50 and 70 percent of its workers from the neighborhood surrounding the facility, offsetting some of the lack of economic potential of the past few decades. The area around the facility had a 20 percent unemployment rate before the pandemic.

At the time of this reporting, they’ve only recruited six of the 100 jobs, with plans to recruit more this fall. The facility is slated to open in January. Five of those six future employees are from the neighborhood.

“These individuals, they do have barriers themselves,” said Trelles Evans, who works on both recruitment and providing wraparound services at Goodwill. (While employees will work on Cook Medical products, they’ll be Goodwill employees.) “So we’ve been coaching them and giving them the wraparound services in hopes that they will blossom into leadership for the new site.”

In addition, Cook Medical partnered with the Indianapolis Foundation and IMPACT Central Indiana to invest money into building the facility, as well as develop a model for more direct community reinvestment. The foundation created a 501(c)2 entity, which owns the building and serves as a go-between for Goodwill’s lease payments on the facility and payouts to the original investors (like Cook Medical and the Indianapolis Foundation). By using that entity to facilitate those lease payments, they expect to have an extra $100,000 a year — which will go right back into community projects.

But they wanted to ensure that whatever that additional money went towards was decided by the community itself. Early on, Cook Medical and Goodwill reached out to Ashley Gurvitz, who runs a community development organization in northeast Indianapolis. She wasn’t immediately convinced.

“Going back to the very first conversation, I just felt like the project seems too good to be true,” Gurvitz said. “There was lots of distrust in the beginning […] One of the first resident perceptions is the fact that developers come in and do things to us, and not with us.”

Gurvitz and her organization take a grassroots approach to community development, whether that means connecting neighborhood residents with home repair help, providing technical assistance to small businesses, or advocating for better local food options. So, she arranged with Cook Medical and Goodwill to bring resident perspectives to the table — from neighborhood association leaders to small business owners in the community. The companies used some community input to shape reinvestment strategy.

One large example of this is the grocery store. Residents raised food insecurity as a significant community concern. The companies invested in already existing efforts to start a locally-owned grocery store. The new store will eventually be community-owned and add about 15-20 additional jobs to the project’s scope.

READ MORE: INDIANAPOLIS ENTREPRENEURS PREPARE TO OPERATE NEW GROCERY STORE FUNDED BY COOK MEDICAL

That was encouraging for Cecelia Dodson, who attended those meetings for the first time more than a year ago and has continued to watch this project develop.

“We’ve had people moving in and out of our neighborhood for years, and that’s kind of not really materialized,” Dodson said of previous development projects, similar to the distrust Gurvitz sees in other residents. “So we’re coming in with sort of a guarded position. We want to work with them as energetically as we possibly can.”

Dodson said she is happy about the new grocery store investment and the follow-through to hire minority-owned contractors, but frustrated by the fact that few in her neighborhood are aware of the project and its potential for jobs.

She plans to get out there and drum up awareness herself.

“We have to speak up when we see it not happening, because we can’t wait until it’s well established over there, and then we have no clout at all,” she said.

For now, she plans to closely watch the project’s progress and is assuming the best — until proven otherwise.

“I’m willing to give them the benefit of the doubt and see what they do,” she said. “But I am not going to be quiet about it and just let it go. Because I’ve been there before.”

Why it’s significant in the big picture

On a national scale, Mark Muro at the Brookings Institution said that a project like Cook Medical’s is a part of a growing business trend to offer better-quality jobs to workers. He pointed to Indianapolis-based OneAmerica’s 2019 project increasing the salaries of 104 positions that did not meet the regionally benchmark for Brookings’ defined “good job” threshold, as well as Evansville-based Old National Bank’s effort to align itself with liveable wages for the region over the course of the next three years.

He said it comes after years of businesses putting profit over labor force satisfaction.

“Many businesses, for many years, have not pursued a ‘good job’ strategy, but rather a ‘bad job’ strategy,” he said.

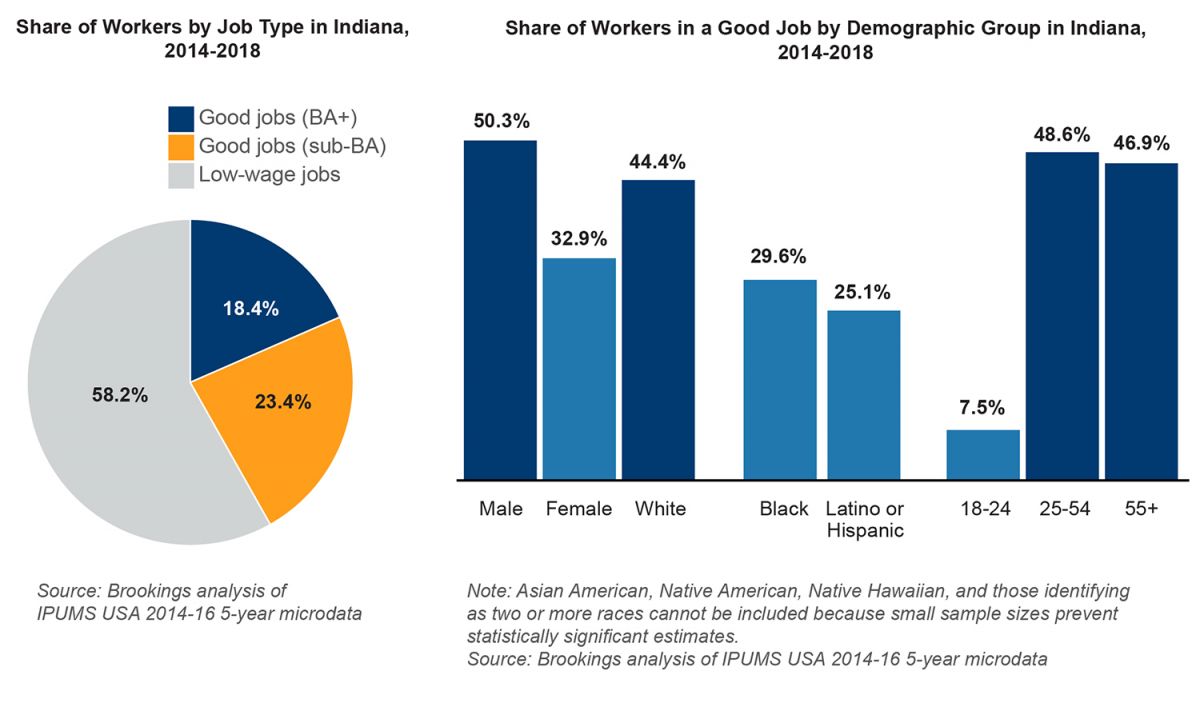

The Brookings Institute defines a “good job” as one that pays a regionally-adjusted wage of $40,700 per year, along with employer-sponsored benefits.

Muro’s research shows that Indiana hasn’t been producing enough “good jobs” at pace with its workforce. That disproportionately affects people who are younger, female, and Black or Latino. But Muro says that companies can produce ‘good jobs’ if they want to. It just requires a different business model.

In Central Indiana, a good job amounts to $37,600 a year, or $18.02 an hour. Cook Medical’s starting wage sits at $15 an hour. Muro acknowledges it still may be lower than ideal — especially in an economy where many employees are looking for more from their workplace in terms of wages and benefits.

“The wraparound services, no doubt, have value,” he said. “There is upward wage pressure now, in the economy for all these various reasons […] they may need to pay more, eventually.”

Still, Muro believes this project stands on the leading edge of this model.

“What I think is interesting here is the kind of multilevel attempt to address the full complexity of moving onto a ‘good job’ pathway,” he said. “This is a very dramatic and complicated effort.”

But there are also broader economic factors at play.

“It’s just one company and one factory in a massive, multi-million worker economy, where the fundamental structures of the economy are still seemingly pushing towards a ‘bad job’ model,” Muro said. “Are they paying enough? And, is it attractive enough? Can they skill up workers sufficiently so that they will stay, and so that they get the productivity benefits that would make this also a business success?”

Looking forward, there’s a lot of optimism

For his part, Cook Medical CEO Pete Yonkman is engaged in those conversations about the shifting nature of corporate responsibility.

“People are starting to ask, ‘what is the role of a company? What is the role of corporations in our communities?’” he said. “I think we have to rethink that a bit.”

Yonkman noted that there are many communities across the state, rural and urban alike, that have lost manufacturing jobs. He hopes that Cook Medical’s new facility offers a blueprint of how other corporations can make similar investments in both themselves and in a local neighborhood.

“Think about the impact that could have on our state — you could really be able to start to think about how do you rebuild the middle class,” he said.

For Scarlett Martin, director of Indianapolis’ Department of Metropolitan Development, the approach is exactly what they’ve been looking for from corporate partners.

“This example of a company working with the neighborhood, alongside the neighborhood, giving neighborhood access to jobs, is the kind of development that we hope we see in other parts of Indianapolis,” she said. “I certainly don’t want to suggest that Cook is the only company that’s really pushing the boundaries. But I think this project kind of goes further than most, because it is so comprehensive.”

Gurvitz hopes this is an approach that can be adapted beyond northeast Indianapolis.

“At the end of the day, I look at it as — if this can be an equitable way of us all building together, I’m for it. Let’s put it in a nice little box, and go take that to every other neighborhood.”

This story was initially published by WFYI, a partner of the Indianapolis Recorder.