Staff members at Martin Luther King Community Center in Indianapolis are asking neighbors to not call the police on Black teens using the center’s facilities.

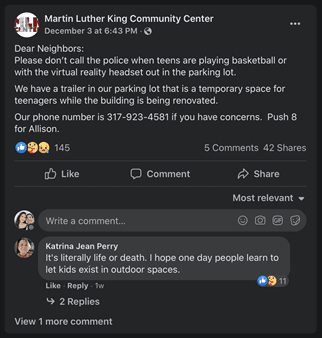

The center posted a message on its Facebook page on Dec. 3, stating: “Please don’t call the police when teens are playing basketball or with the virtual reality headset out in the parking lot.”.

The post came after the police were called on a group of Black teens playing outside earlier that day.

The MLK center is closed for renovations, so the nonprofit is providing services through a temporary trailer set up in the center’s parking lot. Allison Luthe, the executive director, said children come to the trailer to get help with school work, use computers with internet access and play with friends.

On the day the police were called, the kids were playing basketball and using the VR headsets outside by the trailer. Douglas Morris, program director at the center said something unexpected happened.

“I saw a police car sort of dart across the parking lot. There were already two [officers] out of the car walking toward the kids,” Morris said. “So I said, ‘Can I help you gentlemen?’ And so then they turned from the kids and started walking toward me.”

Morris said the officers told him they’d received a call from a neighbor saying children were burglarizing the construction site.

A spokesperson for the Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department said in an emailed statement to WFYI that they received a call from “a citizen concerned about kids playing near the construction site.”

But there was no construction equipment there, Morris said, and the trailer is not part of the building renovations.

Several police cars eventually arrived at the site.

“The whole point of this space is for it to be a space for them to be themselves and do whatever they want to do,” Morris said. “And now they’re being confronted, like they did something wrong.”

After Morris explained to the police that the trailer was set up for the teens to use — and that there was nothing wrong going on — the situation was resolved and the officers left.

But the teens were shaken up. Morris said as soon as the teens saw the police cars coming, they ran into the trailer. For them, it was almost a knee-jerk reaction.

Luthe said it is not hard to see why: These interactions can turn into life-or-death situations.

“Fortunately, they ran into the trailer. You know, if they had run down the street, what would have happened?” she said.

Luthe said this situation was unwarranted, but it does not surprise her. She has seen repeated incidents of the cops getting called on Black teens around the center and Tarkington Park across the street for doing what she describes as “teenage stuff.”

“Sometimes people call the police after dusk when kids are in the park after the time they’re supposed to be,” she said.

Like many U.S. cities, Indianapolis is experiencing the lasting impacts of segregation and racist housing policies. The result is: disparities in education, health, economic opportunity, levels of gun violence and law enforcement presence in communities of color.

Higher levels of policing in Black communities is a concern, Luthe said, because unnecessary interactions between Black children and police can lead to potentially dangerous situations for the children.

Local and national trends point to greater use of force in policing of low-income, predominantly African American communities. Police in Indianapolis use force on Black residents 2.5 times more than on White residents, according to data from SAVI, a data analysis program at Indiana University Purdue University Indianapolis.

The MLK Center and Tarkington Park are located at the intersection of stark racial and economic disparities in Indianapolis. The area has had its share of racial tension, Luthe said. But the center is slowly making progress.

“We’re right next to a condominium tower and half the building probably has my cell phone number, the front desk has every [MLK Center] staff person’s picture and phone number,” she said. “So we’ve done a lot of things to educate the community. What we want to do is be the buffer.”

Still, Luthe said there is a lot of work that needs to be done to address “false assumptions and prejudice” against young Black men and women. Unconscious biases and racism are very much at play, she said, and young Black people are the ones who often pick up the tab.

Luthe’s message to the community is: “When you see young Black men playing basketball at the community center parking lot, then that’s what you should see. You should see them playing basketball and having fun.”

But unfortunately, she said, “not everybody sees them that way.”