In the 1930s, seven Black Indiana University education students were made to finish their student teaching at Crispus Attucks High School in Indianapolis rather than the nearby Bloomington High School. It was a decision that some believed was an attempt by the university to uphold structural racism and anti-Black racial injustices within central Indiana. Jo Otremba, a graduate student at IU and recipient of the Wilma Gibbs Moore Fellowship, hopes to tell their stories.

Pursuing their master’s degree in library science with a specialization in archives and records management, Otremba has always been drawn to maintaining and organizing the tidbits of human life. From photographs to journal entries, to small sentences buried within a mountain of information, these little excerpts, they explain, are what drew them to the field in the first place.

“[Archiving] is what I know,” said Otremba, who is currently in their last semester at IU.

With an hourly job in the graduate program, Otremba began this passion project unexpectedly. Otremba was working on a research assignment, one typically that would result in a blog post online for the school or be a featured article or display case. The assignment was to research a document about two Black education students at IU who were victims of segregation within Bloomington High School’s student teaching program.

“It was very tedious to find the records. Most were hidden under white archives. It’s a culmination of Bloomington Black history and it was a very difficult situation for [the student teachers] to overcome,” said Otremba.

After preliminary research, Otremba was able to uncover the experience of seven Black students and their journeys to Crispus Attucks High School, a bus ride that, as Otremba stresses, was no short distance.

“[For] most of them, there was no record of any stipend or money. Most did this at their own expense to finish their degree because they were forced to,” said Otremba.

One such example of these students was Nathaniel Sayles, both a victim of the segregated student teaching practices and a key figure in an anecdote Otremba says encouraged them to continue their project.

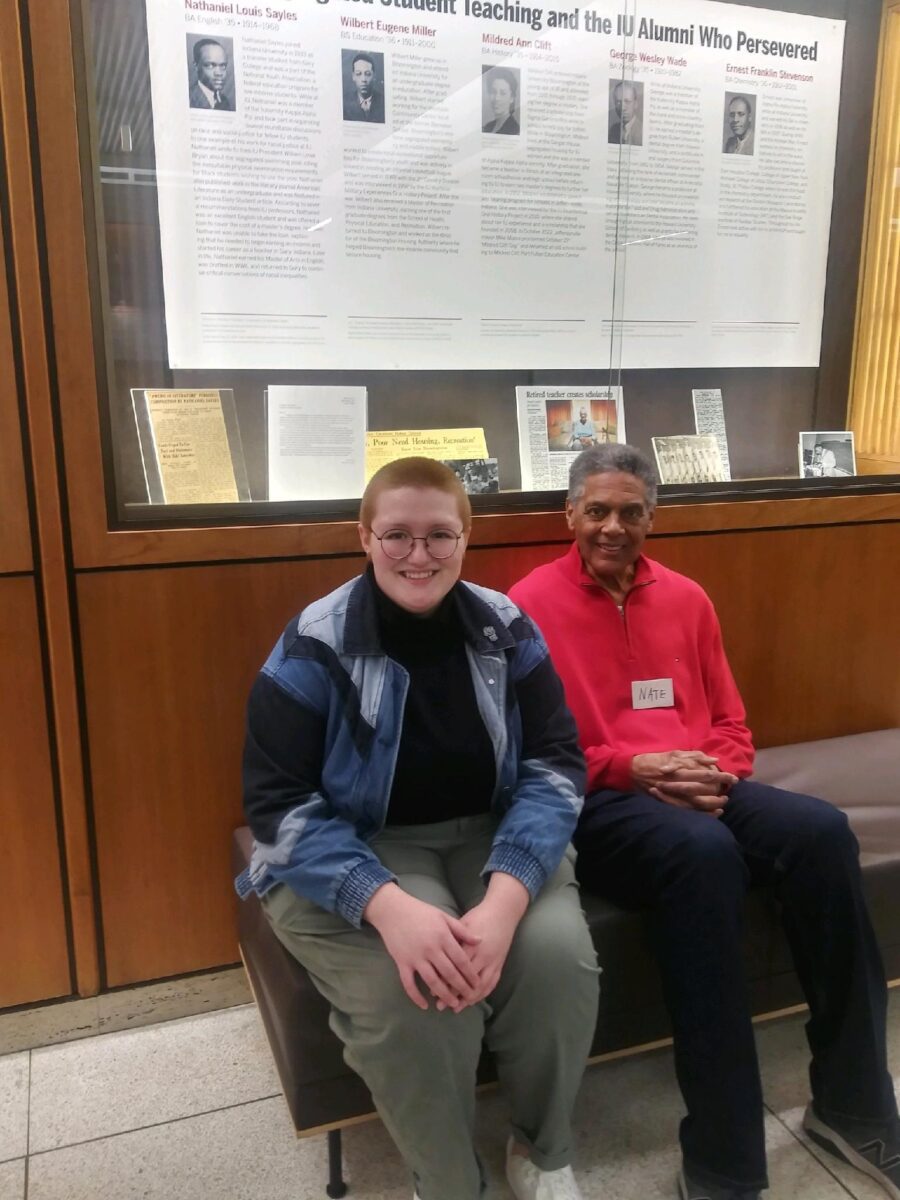

In February of 2023, Sayles’ son and namesake, Nathaniel “Nate” Sayles, came into the lobby of the Indiana University library and was shocked to find an exhibition featuring his father and seven other alumni in a display case by Otremba. The two connected and spoke about Sayles’ work and the segregation he faced. Otremba showed Nate Sayles the documents they found and shared what it meant to them.

“It was one of the most extraordinary experiences of my life,” said Nate Sayles.

While Otremba felt inspired to continue their work and apply for the fellowship, they still felt hesitant about who would feel the work was necessary and wondered if the topic was too niche to have any real-world resonance.

“I didn’t know what audiences would want this research. I realized this research can help people create an identity and create a sense of community. This was sharing a story of a few individuals who mattered to me and who mattered to the community. That’s what archiving is all about,” said Otremba, who came to realize the value and impact of archiving following their work on this project.

Otremba and five other fellows were awarded the Wilma Gibbs Moore Fellowship to continue their work in their humanities-based research projects. This was an award that, as Otremba’s supervisor explains, means a lot to the entire archives department.

“I’m super proud of them,” said Carrie Schwier, the outreach and public service archivist at IU. “There’s so many stories of everyday individuals, some hidden, some not, that sometimes we don’t get to shed light on. Jo has worked incredibly hard.”

Otremba said the $5000 awarded to each of the fellows will help them further explore how segregation impacted the Black population in Indiana in the 1930s and 1940s, and how archivists and librarians can work to ensure Black history is preserved in a meaningful way.

“Hopefully I can change the narrative around archives centering around white men…It isn’t changing history, it’s making it equitable,” said Otremba.

Contact Staff Writer Hanna Rauworth at 317.762.7854 or follow her at @hanna.rauworth

Hanna Rauworth is the Health & Environmental Reporter for the Indianapolis Recorder Newspaper, where she covers topics at the intersection of public health, environmental issues, and community impact. With a commitment to storytelling that informs and empowers, she strives to highlight the challenges and solutions shaping the well-being of Indianapolis residents.

To answer some questions about my research, all the students in my primary source search are Black students. This article covers my early work and now with the research time afforded through the Indiana Humanities funding, the number of Black student names that did their student teaching in Crispus Attucks is close to 50. I can include my original blog posts about my research in links below. To clarify about the schools that the students were able to complete their student teaching requirements, IU Bloomington Black students were only allowed to do their teaching at the segregated school, Banneker. The school only taught up to grade 8 and students who needed their student teaching for secondary schools were not allowed in the Bloomington High School and then were told they must do their teaching at Crispus Attucks High School. I will have more research out soon as I am currently writing my primary source analysis and I will be happy to share that with anyone interested as it is released.

https://blogs.libraries.indiana.edu/iubarchives/2023/02/22/1930s-segregated-student-teaching-part-3/

https://blogs.libraries.indiana.edu/iubarchives/2023/02/03/1930s-segregated-student-teaching-part-2/

https://blogs.libraries.indiana.edu/iubarchives/2023/01/27/1930s-segregated-student-teaching-part-1/