As the community comes together to celebrate Black History Month, the Recorder is shedding a light on a few of the Black visual artists who paved the way for events like Meet the Artists, Art & Soul and BUTTER.

While Indiana Avenue was known as the nexus for Black musicians and creatives, Black painters, illustrators, sculptors and photographers did not have the same luxury and often worked out of their own homes, turning attics or basements into studios and selling their work on the street, painter Roderic Trabue told the Recorder.

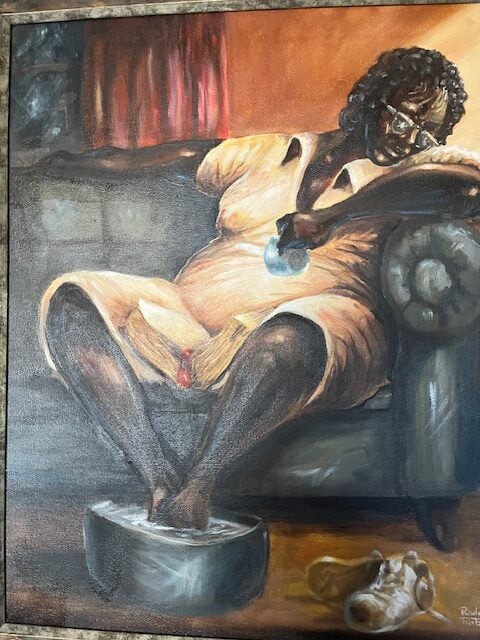

Trabue, a retired educator and founder of Urban Arts of Indianapolis, Inc., grew up on Indy’s Southside, where he spent his time drawing on any piece of paper he could find. He graduated from Indiana State with a degree in art education and went on to teach in public schools during the “Black is Beautiful” Movement in the 1970s.

“The stuff they’re doing now is more or less a celebration of Black culture,” Trabue said. “Back then, I think we was [sic] just depicting Black culture, more than anything. Nowadays, it’s a celebration, and they’re doing some great stuff.”

Laying the groundwork

John Wesley Hardwick and William Eduoard Scott were prominent Black Indy-based painters in the early 1900s, Trabue said. Both attended Herron School of Art and Design, and their work, which features landscapes, still life portraits and murals, was heavily influenced by African and Haitian themes.

RELATED: Art & Soul kicks off Black History Month ahead of NBA All-Star

These themes seemed to trickle down as many of the Black artists of the 1960s, 70s and 80s — such as Joseph Holiday, William Rent, John Andrew Spaulding, Terry Clark, Carol White, Mae Alice Starks Engron and Felrath Hines — were also creating works with primarily African and Black cultural themes, Trabue said. Because of this, he said their work was often deemed “too ethnic” or “too Black” and not welcomed in local art exhibitions or galleries.

Holiday, the Black painter most known for his “Black Jesus,” was one of the main influences on Indiana Avenue and one of Trabue’s own personal influences.

“Joe was just terrific. He was a great artist, and with his influence, I really got into doing what we call ‘Black art,’ if you will,” Trabue said. “Joe’s work was quite well known down the avenue; he’d do a lot of stuff down there. He used to just walk around and sell his work for $10.”

D. Del Reverda-Jennings, an Indy-based multidisciplinary artist and gallerist, spent the last three decades working to cultivate and empower artists across all disciplines “to ensure that underrepresented artist’s works are exposed to the public and by offering current information, documentation and opportunities to assist in a creative’s desire and pursuit to propel their artwork to the forefront of the arts mainstream.”

Del Reverda-Jennings and Trabue named William Rasdell and Carl Pope as well known Black photographers whose work was believed to go beyond the borders of Indiana and ease more people into appreciating Black artists.

Since 1990, Pope’s work has been featured in the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago and the the Museum of Modern Art, Del Reverda-Jennings said. Rasdell, who passed away earlier this year, worked primarily on Indiana Avenue and frequently photographed the Madam Walker Legacy Center both presently and during the 1970s and 80s when it stood abandoned, Trabue said.

Making Black spaces

Trabue and Del Reverda-Jennings both said Indy’s Black artists stepped up and created opportunities for themselves. In 1971, during the first Indiana Black Expo, Black artists from Indianapolis and across the country were invited to showcase their work in an exhibition with support from Mary Mumford and William and Gilbert Taylor.

In 1998, Del Reverda-Jennings created FLAVA FRESH !, an annual national, multi-exhibition juried contemporary art show, during a time when there were only two other venues in the state focused on Black artists.

However, she said true awareness of the Black arts scene in Indianapolis did not come about until the late 1980s when the Indianapolis Marion County Public Library’s 1987 presentation for Black History Month included a showcase of Holiday’s paintings. Anthony Radford, artist and library employee, was also given the opportunity to showcase his work alongside Holiday and local artists and became founder and curator of Meet the Artists.

READ MORE: Meet the Artists XXXVI is here

“The event was well accepted by the community who wanted more,” Del Reverda-Jennings said in an email to the Recorder. “The annual gala celebration and exhibition of African American art has thrived to become an annual tradition each February.”

Art & Soul, presented by the Indy Arts Council, came on the scene in 1996, giving local Black artists across various disciplines the opportunity to showcase their work in the Indianapolis Artsgarden before expanding in 2010 to include venues like The Jazz Kitchen and Gallery 924.

Common themes in contemporary Black artists’ work, which run parallel to artists’ work of the past, include family, belonging, figurative pieces, racial discrimination, hatred and unjust social issues, Del Reverda-Jennings said. She also said many of the same challenges that existed for artists of color in the late 1960s still exist today.

“There are very few brick-n-mortar gallerists or dealers of color in Indiana. There has been progress, but we linger far behind our white peers and colleagues,” Del Reverda-Jennings said. “Most AOC/BIPOC artists are hampered by a lack of representation, resources, materials, supplies, lack of support, and the ability to afford what can be considered a commercial studio, where the public can view their work in a more personal context.”

In 2020, Black artist group The Eighteen Art Collective were invited to paint a Black Lives Matter mural on Indiana Avenue. In 2021, cultural development firm GANGGANG hosted the first BUTTER, an equitable fine art fair for Black artists, and continued each year since.

It is progress, Trabue said.

Without the activism, advocacy, proactive consensus, allies and effort, artists of color would be back to being almost invisible, Del Reverda-Jennings said.

This story has been updated with the correct date and location of the first Art & Soul and spelling of D. Del Reverda-Jennings.

Contact staff writer Chloe McGowan at 317-762-7848. Follow her on Twitter @chloe_mcgowanxx.

Chloe McGowan is the Arts & Culture Reporter for the Indianapolis Recorder Newspaper. Originally from Columbus, OH, Chloe has a bachelor's in journalism from The Ohio State University. She is a former IndyStar Pulliam Fellow, and has previously worked for Indy Maven, The Lantern, and CityScene Media Group. In her free time, Chloe enjoys live theatre, reading, baking and keeping her plants alive.