Why DEI works for business

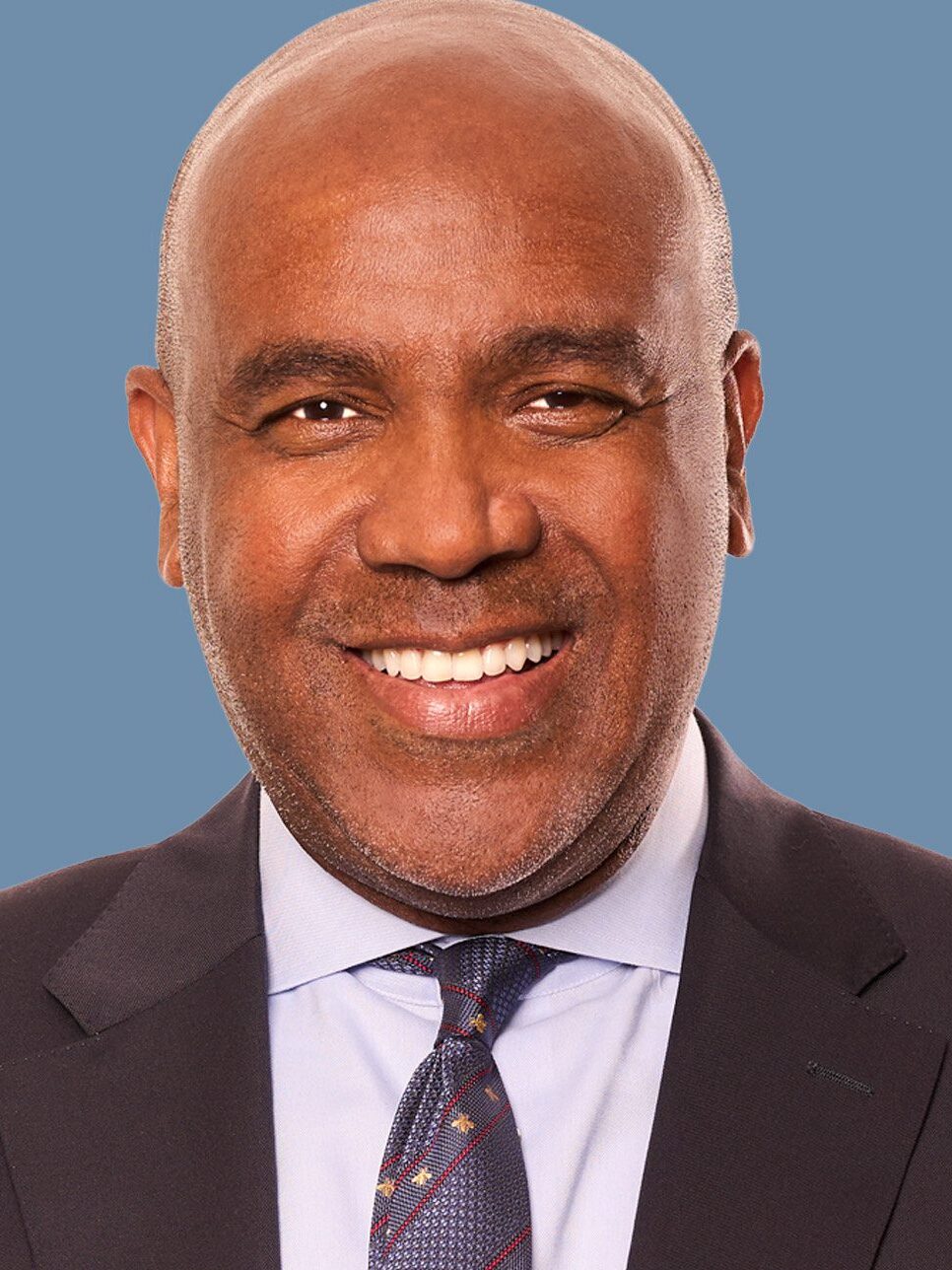

By ROD COTTON

Perhaps it’s no coincidence that the tumultuous events of the past few weeks fell on the eve of Black History Month.

Though many of us knew about the administration’s promise to end diversity programs, the White House order on Jan. 20 felt like a giant step back. The next week, the freeze of $3 trillion in federal grants and temporary shutdown of Medicaid programs amplified the chaos. The next day, Medicaid programs across the country temporarily lost access to federal payment portals. These changes are affecting people’s health and opportunity to succeed. What setbacks will we wake up to tomorrow?

As a former health care executive at Roche Diagnostics and a champion of board diversity, health equity and eliminating health disparities, this state of affairs is beyond discouraging — but it’s not surprising. Like many of you, I’ve been through this before. Along with disappointment, I feel a sense of resolve. Throughout my life, I’ve seen great achievements come from hardship and suffering. That’s why now more than ever is the time to reflect on our history — to remember where we came from and how far we’ve come. It’s a time to arm ourselves with knowledge and share it.

In that spirit, and in celebration of Black History Month, I’d like to share a little of my own history. This story of a little boy from South Central LA reminds me just how far I’ve come, and how access to opportunities helped me build the career I’d always dreamed about.

Access to success

I grew up in Los Angeles in the 1960s and ’70s, a period marked by activism, legal changes and often violent confrontations. Three events in the 1960s shook me to my core and made me realize what my life would be like.

- In 1965, when my parents, my cousin Donald and I were returning to Los Angeles from a camping trip, police stopped our car and held us at gunpoint. We’d returned to town during the Watts Riots.

- Three years later, the assassination of Martin Luther King hit my Alabama-born parents hard. I still recall my mother’s tears that day.

- In the 1970s, school integration put me on a daily ride that changed my life. I was bussed from my home in South Central Los Angeles to Palms Junior High School in Culver City, Calif., and later to Birmingham High School in Van Nuys, Calif.

Being bussed to faraway schools wasn’t exactly a handout. I caught the bus in my neighborhood at 6:30 a.m. and returned home at 6 p.m. In Culver City, my classmates made fun of my brightly colored, mismatched clothes. They used to stand in a circle around me and call me “Christmas tree.” My junior high math teacher called me “dumb” and gave me a “D” in his class until my mother, also a teacher, showed up and gave him a piece of her mind. After that, he treated me differently, and I finished the course with an “A.”

Going to school in a more affluent neighborhood than my own gave me the opportunity to visit friends with different backgrounds. My buddy Josh, the son of Hollywood executives, lived in Encino. Growing up in a solidly middle-class Black neighborhood, I’d never seen a home like Josh’s: a mansion with a valley view, a pool and matching Lincoln Continentals in the driveway.

Thus began my access to a different world and a cultural education that would serve me throughout my career. At the University of California, Santa Barbara, where I earned my B.A. in biological science and sociology, I was part of a tiny population of Black students that remains small to this day and may become smaller. Thanks to my experiences in high school, I knew how to comport myself in diverse social settings. That helped me in grad school, as I began my career in health care and all along the way, because I was often the only Black person in the room.

Through it all, I relied on my mother’s teaching.

She said: “Things will be different for you, so get over it! You’re going to have to work twice as hard as everyone else to get where you want to go, but everything you learn, everything you do — no one can take that away from you.” This philosophy led me to strive for excellence — even perfection. The biotech industry is fiercely competitive, and my performance was based on metrics and sales figures. There simply wasn’t room for mediocrity or an erosion of standards.

The bottom line

My opportunity to succeed began on that school bus in junior high. Like Michelle Obama and many others of my generation, having access to a “school of high expectations” gave me a chance to leverage my strengths and compete for the positions that launched my career and led me to the C-suite and boardroom.

A connection with an on-campus recruiter at UC Santa Barbara helped me land my first job as a sales rep with Burroughs Wellcome Pharmaceutical Company (which later merged with another company to form GSK). Though I later faced discrimination in that job while calling on doctors in affluent white areas – receptionists at some doctor’s offices wouldn’t let me in the door once they saw the color of my skin – I had a start.

What will the future look like for young, talented Black people who don’t have the opportunities I had? Where would I be now if I hadn’t had those opportunities?

As wealth manager Christopher Gandy recently posted on LinkedIn, true equality requires a shift in culture that acknowledges historical disparities and gives everyone – men, women, all races, all creeds – an equal opportunity to succeed.

Now is the time to give each other grace, hold on to hope and work together toward solutions. Epidemiologist Katelyn Jetlina gives this advice: Even small actions — calling a friend, connecting with others, sharing a story — can ripple outward.

Black is beautiful for business

If you find yourself in a discussion about why it’s important that each of us have an equal opportunity to succeed, it may be helpful to share DEI’s practical benefits. Here’s a checklist of DEI’s advantages from a business perspective.

It improves quality

Serving on boards in the health care and biotech industries, I’ve experienced firsthand the power of making a difference as the only Black voice in the room. The perspective I add as a senior executive — and as an African American — is powerful. When I speak up, my words have an impact because of my audience and my experience. The same is true for other people of color.

Diverse representation also plays a part in the performance of pharmaceuticals and other therapies. It all starts with clinical trials. Here’s an example: Non-Hispanic Black women experience a higher prevalence of preeclampsia compared to other groups. If a pharma company or researcher is testing treatments for preeclampsia and doesn’t select a diverse group of women for the trial, it can become difficult to validate results. Studying the disease across diverse populations ensures treatment effectiveness is applicable to all women at risk, not just a specific group. That promotes better health care for everyone

For Black people, the matter of diverse clinical trials truly is urgent, especially with cancer research. For all cancers combined and for most major cancers, Black Americans have the highest mortality rate of any racial and ethnic group.

I’ll share more thoughts on the topic of board diversity in an upcoming interview with Mary Smith, in light of the recent ruling of the Fifth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals to strike down Nasdaq board diversity rules.

It increases productivity and performance

The stats tell the story, and people who work with me know I like to share them:

- A McKinsey and Company report notes a 39% increased likelihood of outperformance in companies for those in the top quartile of ethnic representation versus the bottom quartile.

- According to research, companies with diverse workforces tend to have up to 2.5 times higher cash flow per employee compared to less diverse organizations.

From a boardroom perspective, I’ve seen the power of diversity in real time. If you add one woman to a board, you have diversity in the boardroom. If you add a second woman, you’ll see even more diverse thought. The more diverse the boardroom, the more diverse the thought. If your board is homogenized, you get groupthink.

It’s profitable

JP Morgan Chair and CEO Jamie Dimon, who, like many leaders, stood by corporate diversity initiatives, called the company’s community outreach efforts to the Black, Hispanic, LGBTQ+, veteran and disabled communities “90% for-profit.”

“Wherever I go, red states, blue states, green states, mayors and governors said they like what we do,” Dimon said. “We’re very proud of what we’ve done, and what we’ve done is lift up cities, schools, states, hospitals, countries, companies — and we’re going to do more of the same.”

It builds a better talent pool

DEI policies aren’t perfect. Neither is the way we handle finance or HR or any number of business practices. The goal is to root out inefficiencies and glut and make things better. Fine-tuning diversity policies is good business. Wiping out opportunities to hire the best, brightest and most talented people for the job is not.

Mark Cuban, the entrepreneur, venture capitalist and minority owner of the Dallas Mavericks, has been speaking up about this topic. “DEI doesn’t mean you don’t hire on merit,” Cuban said. “Diversity means you expand the possible pool of candidates as widely as you can. Once you’ve identified the candidates, you hire the person you believe is the best.”

This practice is especially important when you consider that, although American businesses are creating hundreds of thousands of jobs each month, a significant number of positions remain unfilled. In Indiana, government officials are building programs and changing policies to build a workforce for the future. For example, Indiana needs to grow and develop the state’s tech workforce by an additional 41,000+ tech workers by 2030. TechPoint’s analysis shows that talent is evenly distributed in the state, but opportunity is not.

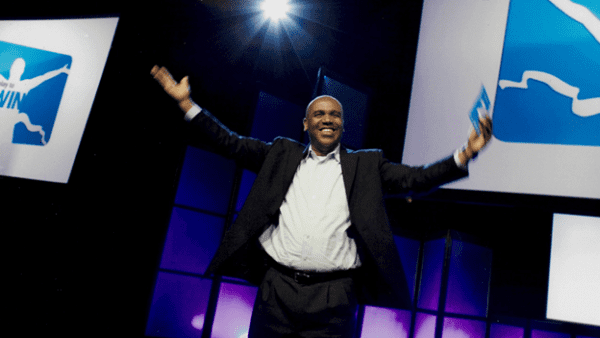

It improves innovation

I saw this firsthand at Roche, especially during and immediately after the Covid-19 pandemic, when our team and company accelerated six groundbreaking products in 11 months. To get there, we ignored hierarchy and used diverse hiring practices to add hundreds of people to our team. We transformed our culture and operations to deliver results like never before — in both business and public health.

One of my favorite stories about diversity and innovation stars Michael Jordan, whose symbiotic relationship with Nike helped grow two of the most popular sports brands in the world. Famously, Jordan’s mom encouraged the Chicago Bulls rookie to sign his first sneaker deal with Nike in 1984. Thus began a partnership that paved the way for athletes to make millions from sponsorships and endorsements. Jordan had a voice in his namesake shoe’s success. In the late 80s, when he asked for more design control, a collaboration with designer Tinker Hatfield transformed Air Jordans into a luxury item, not just shoes you’d wear to the gym — a pivotal innovation. Jordan’s partnership with Nike continues to this day and is considered one of the most successful in sports history, encompassing entertainment, fashion and lifestyle.

It made Jordan the first billionaire player in NBA history, with an estimated net worth of $3.5 billion — and it made Nike billions, too.

A version of this article was published by Rod Cotton on LinkedIn on February 3, 2025.