A public dedication ceremony commemorating the lynching of John Tucker will take place Sept. 30.

It is not a pleasant story, but it is important to acknowledge the historical lynching of John Tucker that took place on July 4, 1845, and the aftermath that followed, Historian Leon Bates said.

Bates combed through historical records and documents of the lynching to submit an application for the state marker. This is the third marker Bates has helped install in Indiana.

“These people were not necessarily in the history, which is another whole discussion. But what they did does warrant recognition,” Bates said.

The lynching of John Tucker was one of at least 19 racial terror lynchings that occurred in Indiana as recently as 1930, according to the Indiana Historical Bureau.

The marker will be dedicated Downtown along the Cultural Trail, near the northwest corner of Washington Street and Illinois Street— the same location where John Tucker was murdered.

Karen Christensen, co-chair of the Indiana Remembrance Coalition, agrees that acknowledging racial violence may be uncomfortable, but it is an important conversation to have.

“Our mission is really making sure the full and complete truth is told about our racial history. That includes not only celebrating things from the Black community that others have ignored over time, successes and things like that, but it also means pulling forward some of this violence and these tragedies that have taken place that we would rather bury,” Christensen said. “We fully recognize people coming into these conversations uncomfortable, but we pursue. We have to move on, we have to talk about it and we have to bring these things to life. That trauma is really still with us in some way or another and in some people more so than others. Trauma still exists within our community.”

The text for the state marker will read: “Lynching of John Tucker.” John Tucker, a local farmer, was born enslaved in Kentucky ca. 1800 and later obtained his freedom. He moved to Indianapolis by the mid-1830s, where he raised two children. On July 4, 1845, white laborer Nicholas Wood physically assaulted Tucker as he walked along Washington Street. Tucker defended himself against Wood’s attack while retreating up Illinois Street. A large crowd watched as Wood and two other men beat Tucker to death. Wood was convicted of manslaughter, a rarity in an era when Black Hoosiers could not testify in court. Wood served three years in prison; the others served no time. Lynchings in Indiana from the mid-1800s to 1930 intentionally terrorized Black communities and enforced white supremacy.

The story of John Tucker

John Tucker was a free person of color, farmer, father of two and husband. He lived with his family in a house near the intersection of St. Clair and Delaware Streets.

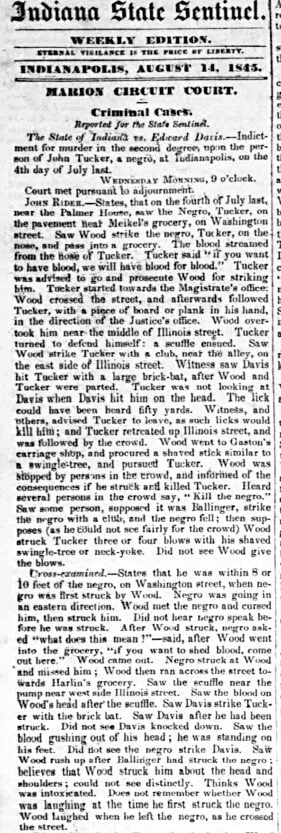

Tucker was making his way home from a city celebration at what is now Military Park when he encountered three white men who eventually bludgeoned him to death as a crowd looked on. Nearly 40 witnesses testified at the trial for his murder.

Witness reports vary on what, if anything, happened before the dispute, but it is widely agreed through the courts that the physical confrontation began when one of the men hit Tucker, causing his nose to bleed, according to Bates.

Two of the three men were arrested, while the third was never apprehended. The lynching of John Tucker is significant because it was one of the rare times a white man was tried and convicted for the lynching of a Black man. However, he only served three years of hard labor, Bates said.

Christensen said it is important that people understand the history of racial inequity in order to acknowledge how it continues today.

MORE FROM THE RECORDER: Local historians call for full archeological dig before Henry Street bridge plans are finalized

“If you look at what actually happened to John Tucker, there have been events, very recently, a lot like this. So, it begs the question of ‘Have we learned anything about our racial past?’ And I think the answer is very, very little,” Christensen said. “So, we think it’s important for people to understand where we’ve come from so that they can understand where we are currently. And honestly, we think that it’s important for the Black community to feel like their story is being told because that often doesn’t happen.”

Many Black community members in Indianapolis remembered the weak legal response to the case for decades following the trial.

Rev. Henry Ward Beecher wrote in the Indiana State Sentinel, “I never saw a community more mortified and indignant at an outrage than were the sober citizens of this. Some violent haters of the blacks, the refuse of the groceries and a very few hair-brained young fellows indulged in inflammatory language.”

He also noted that Tucker was “very generally respected as a peaceable, industrious, worthy man.”

Contact staff writer Jayden Kennett at 317-762-7847 or by email jaydenk@indyrecorder.com. Follow her on Twitter @JournoJay.