Local historians and community members are asking city officials for a full archeological dig of a long-forgotten Indianapolis graveyard before the designs for a new bridge are finalized.

City officials announced May 9 that they will extend the Indianapolis Cultural Trail by expanding one mile of trail near Lucas Oil Stadium and by adding a contentious yet-to-be built bridge on Henry Street.

Local historians are worried that a piece of Black history will be destroyed if construction of the bridge is finalized. Director of Indiana Landmarks Black Heritage Preservation Program Eunice Trotter said bulldozing the cemetery to build the bridge is “a blatant disregard for Black heritage and Black souls.”

The Indiana Landmarks program, which supports statewide efforts to recognize documented and undocumented Black heritage by identifying places that should be listed in the National Register of Historic Places, believes that the “Colored Cemetery” at Greenlawn Cemetery is the largest burial site of African Americans in the state. As a result, the organization has identified the cemetery at Greenlawn as eligible for the National Register.

Historians and community members would like to see an archaeological dig of the area with interpretative signage, memorials and grave markers, she said.

“The thought of posting an archaeologist to watch for signs of burials as the area is bulldozed is one of the most ridiculous propositions I have heard,” Trotter said. “If the City of Indianapolis allows this site to be desecrated in this manner, then the city will be complicit in the erasure of Black heritage.”

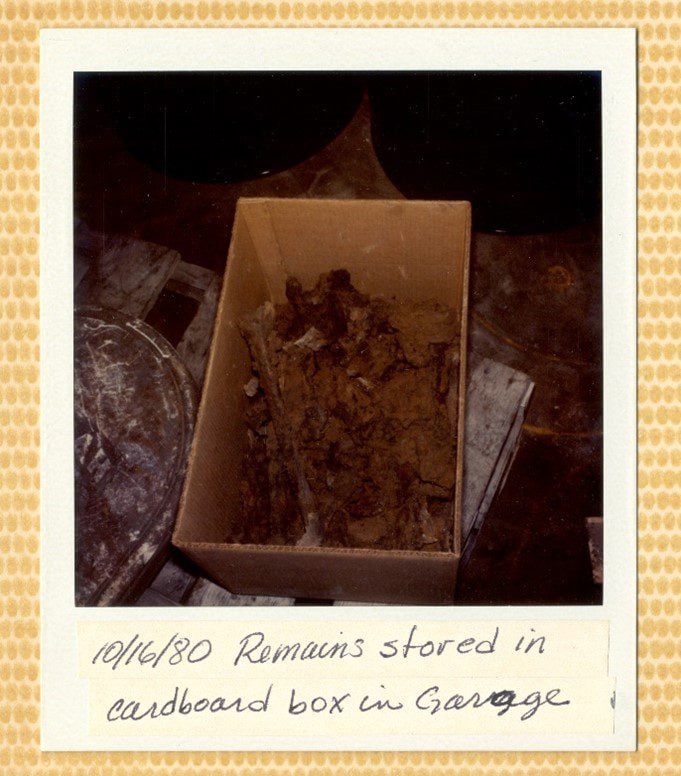

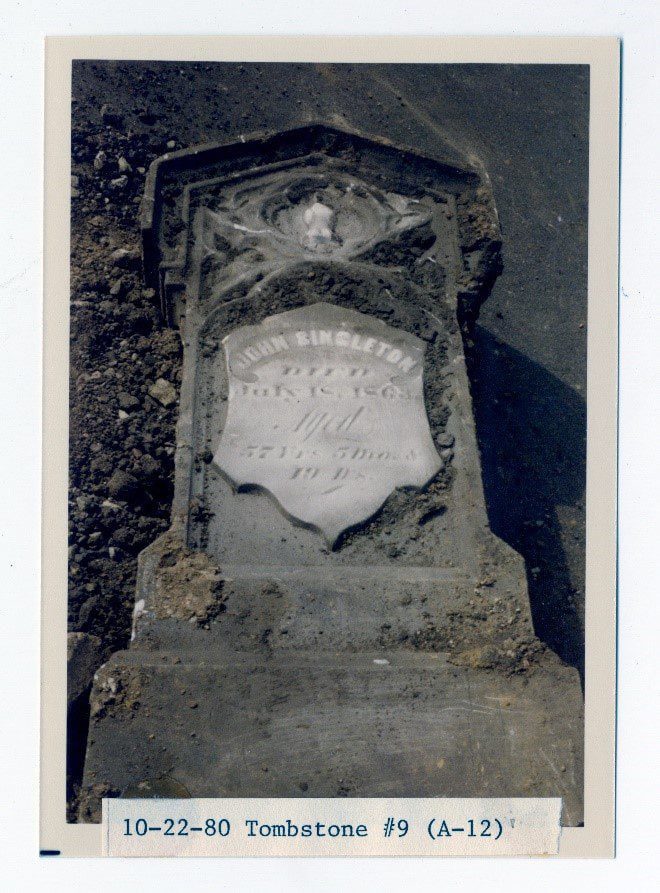

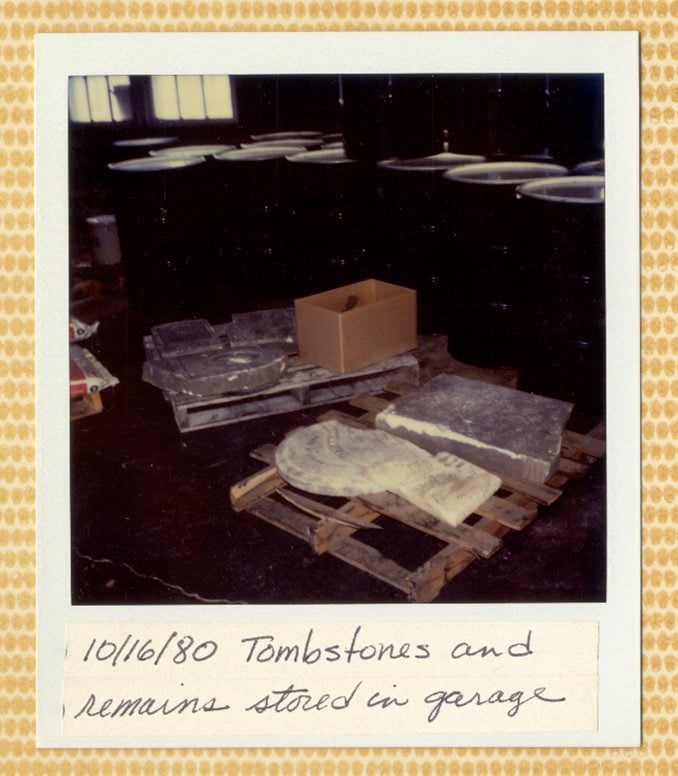

Four different expansion projects have uncovered forgotten pieces of the cemetery, according to an article published by the Indianapolis Star during the most recent discovery, which was in the 1980s. Casket handles, headstones and corpses have been uncovered over the decades on the plot of land, reminding the Black community that their history continues to be erased and rebuilt upon.

The History of Greenlawn Cemetery

Once a bustling business, the “Diamond Chain” factory complex now sits abandoned near the northwest corner of South and West Streets. Before the 102-year-old facility Downtown closed and relocated, the land was once home to Indianapolis’ first cemetery, Greenlawn Cemetery, according to the Genealogical Society of Marion County.

The far west end of the area along the White River was a segregated area where African Americans were buried throughout the 1800s, historian Leon Bates wrote in a report. Some graves have washed out due to rain and flooding throughout the years, and others have been relocated to Crown Hill Cemetery and Floral Park Cemetery; however, “no major improvements” have been made to uncover what’s really left of the cemetery, Bates said.

The exact number of graves, their location and the identity of who may be buried there is unknown due to records being lost or destroyed over the decades, he said. However, “it is a given” that numerous prominent members of the three largest Black churches in Indiana were once buried there, including Chaney Lively, the first known African American resident and landowner in Indianapolis and founding member of Bethel A.M.E Church, according to Bates.

John Tucker, the victim of a historical lynching that had a strong impact on the Black community in Indianapolis, is also believed to have been buried at the cemetery. Tucker was an early resident and member of Bethel A.M.E Church and was beaten to death at Illinois and Washington Streets by three drunken white men. Tucker’s case is believed to be the first of its kind where a white man was tried and convicted by a jury.

Several members of the 28th United States Colored Troops, Indiana’s only African American soldiers of the Civil War, were originally buried at the cemetery as well. More than 2,000 members settled on the Southside of Indianapolis and were founding members of St. Mark African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church (A.M.E Zion Church) and Penick Chapel A.M.E Zion Church.

While many graves were relocated after the closure of Greenlawn, not everyone interned was relocated, Bates said.

“Thus far, no records have been located that suggest that the ‘Colored Section’ of Greenlawn Cemetery was ever carried out. The burial of African Americans outside of the Greenlawn fence and the lack of documentation are perfect examples of the erasure of the African American experience,” Bates said in his report.

What’s Next?

The City of Indianapolis said its team of consultants and contractors are making “every effort to proactively proceed in full compliance with all relevant state and federal regulations protecting burial grounds.”

No human remains have been found when testing soil samples for bridge support locations, the city said. Indiana law will also require work within 100 feet of human remains, burial objects or grave markers if they are discovered.

The Indiana Department of Natural Resources’ Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology are responsible for overseeing the archaeological work and would be notified within two business days of a discovery, according to Indiana Code.

A few dozen people joined historians in asking the city for a full archeological dig of the cemetery at a public meeting May 9, including director of Historic preservation at Crown Hill Cemetary Jeannie Regan-Dinius and members of the Indiana Remembrance Coalition.

Although city officials plan to create a citizen advisory board for the project, no details are set.

The designs for the bridge are expected to be complete in August.

Contact staff writer Jayden Kennett at 317-762-7847 or by email JaydenK@indyrecorder.com. Follow her on Twitter @JournoJay.