As noted in part one, Crispus Attucks High School was designed to be the segregated high school for Black teenagers in Indianapolis. The school served that purpose for decades until Indianapolis Public Schools desegregated its high schools.

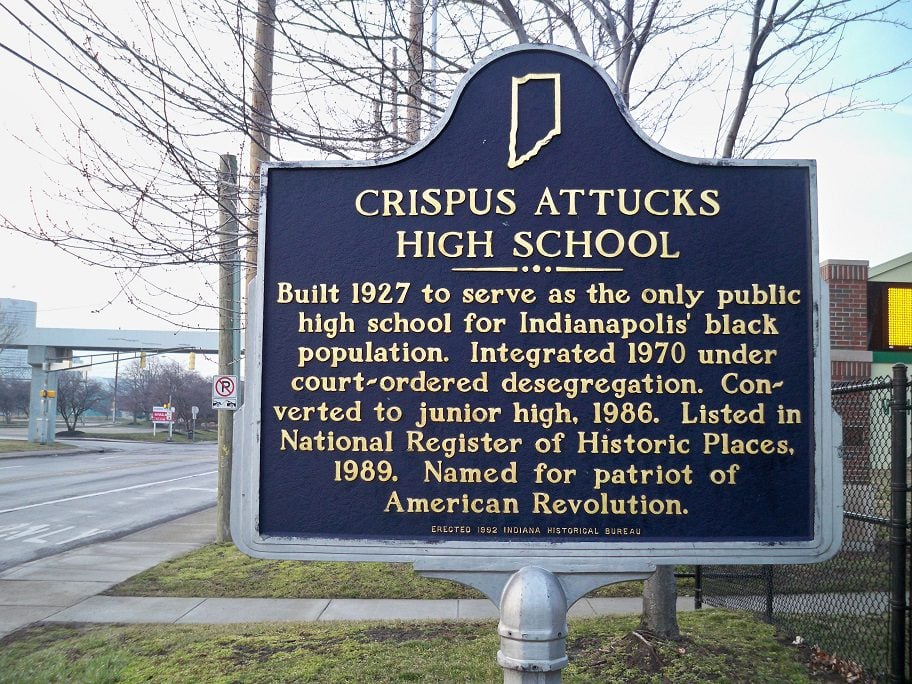

According to the registration form seeking historical status filed with the National Park Service on Oct. 15, 1987, the three story, brick structure opened to students in 1927 and was expanded twice. Additions were placed onto the initial structure in 1938 and in 1966. In 1989, Crispus Attucks High School was added to the National Register of Historic Places.

While a high school for most of its history, this structure served junior high school and middle school students from 1986 to 2006. Today, students of all races are educated at this school in grades 9 through 12. Specialized educational programs are available for students in health sciences and education.

“Despite the opposition of the Better Indianapolis League, a civic organization of progressive Black citizens, prominent Black citizens, and Black churches, the [Indianapolis] school board voted unanimously to build a separate high school [for Black students] in [December of] 1922,” according to the National Park Service. “Archie Greathouse, a Black community leader, held up construction with a series of court challenges, but the school board prevailed. The board decided to name the new school ‘Thomas Jefferson High School’ [in June of 1925].”

Many in the Black community opposed naming the new school after Thomas Jefferson. They noted that while Thomas Jefferson was the third president of our country, he also owned human beings as slaves.

Both Crispus Attucks, a former slave, and Paul Laurence Dunbar, a Black poet, were suggested as alternative individuals to be namesakes for the new high school. It was noted by Indianapolis school leaders, though, that an elementary school was already named after Paul Laurence Dunbar. It should be noted that leaders of the Indianapolis schools did not have a problem with two schools with the “Thomas Jefferson” name; there was already a school named after Thomas Jefferson in operation in Indianapolis at the time the new segregated high school was being built.

The National Park Service noted there were “… numerous petitions [starting in February of 1926] to change the name to ‘Crispus Attucks High School’ in honor of the former slave killed in the 1770 Boston Massacre, who is generally considered the first to die in the American Revolution.” According to a news article dated March 27, 1926, in The Indianapolis News, the “… Colored Parent-Teacher Association [reported]…that the name of Crispus Attucks was the most favored [name] by the colored people of the city.”

Prior to considering Thomas Jefferson, Crispus Attucks, and Paul Laurence Dunbar as potential names for the new segregated high school, the initial name considered was Roosevelt High School. This was to honor President Theodore Roosevelt. School board members, according to a news article dated July 1, 1925, in The Indianapolis Star, “… refused to accept the recommendation of … Roosevelt for the new colored high school.”

After all of the discussions, petitions, and meetings, the name Crispus Attucks High School was approved by the Indianapolis school board.

Even prior to opening, the concept of this new high school being “separate but equal” to other high schools was known to be a lie. A news article dated Aug. 17, 1925, in The Indianapolis News, stated “Indianapolis will build the new West Side High School for $416 a pupil and the new Jefferson (colored) High School for approximately $400 a pupil…”

That approach was considered perfectly legal at the time.

On May 16, 1924, The Indianapolis News reported a judge in Marion County ruled “… the segregation of Negroes was constitutional, that ‘disparities in distance and material grandeur are immaterial, and that courts can not interfere with courses of study prescribed consistently to law.’”

Given the reality of the day, many Black individuals and families worked to make the school as successful as possible.

“The high school became a strong source of pride in the Black community when it opened in 1927, despite initial opposition,” the document from the National Park Service continued. “Though taxed for space and equipment, faculty was the best available, hired from traditionally Black colleges in the South. Students were taught a special course in Black history as well as the usual subjects.”

The front page of the Indianapolis Recorder highlighted positive aspects of the Crispus Attucks High School in a news article dated Sept. 10, 1927. “The school authorities are to be congratulated on the type of the faculty selected,” the news article reported. “Practically all of the large colleges and universities are represented and outstanding results are expected from the teaching force. We feel certain that our boys and girls will be well taken care of from the point of view of instruction.”

The news article went on to comment that the school was “…wonderfully equipped by the [School] Board…” and that parents will be “delighted” that the school board was providing sufficient musical instruments for the students to have their own band and orchestra at the school.

The document from the National Park Service explained that “School segregation was outlawed in Indiana in 1949, but the student body remained almost exclusively African American until the 1970s, when busing for racial integration began.”

While Black high school students were able to attend other high schools as Indianapolis Public Schools desegregated through the 1950s and 1960s, Crispus Attucks High School remained as a high school with only Black students for decades. The State of Indiana indicated “…1971 is a more accurate estimate…” of the date when Crispus Attucks High School was actually desegregated.

Note: One item that is not yet clear involves information detailed in a news article dated June 15, 1925, on page 20 in The Indianapolis News: “The [Indianapolis School] board authorized the sale of the old colored high school site to R. L. Britfenback for $70.” It is not certain where the site of this school was located and whether it was simply a site set aside at some point for a future “colored high school,” whether it was a piece of land at what became the site of the Crispus Attucks High School that was not needed for the new high school, whether it actively operated as a “colored high school,” or whether it involved something else.

Do you have questions about communities in Indianapolis? A street name? A landmark Your questions may be used in a future news column. Contact Richard McDonough at whatsinanameindy@usa.com.